Editor’s note: this was first published by Mad in America on 27th July

In 2015, when Norway’s Minister of Health, Brent Høie, ordered the country’s four health districts to set aside beds for “medication-free” treatment, it served as a clarion call for wholesale change in psychiatry, both within Norway and internationally. This was a government decreeing that psychiatric patients should have the choice to be treated without psychiatric medications in a hospital setting, or if they were already taking such medications, to receive inpatient support for tapering from the drugs.

With this call for change in the air, Mad in America in 2017 reported on a six-bed ward at Asgård Hospital in Tromsø, Norway, where patients with psychotic diagnoses were now being treated in a “medication-free” environment. Our headline captured the far-ranging impact this initiative could have, not just in Norway, but internationally: “The Door to a Revolution in Psychiatry Cracks Open.”

That was one of our most well-read MIA Reports ever, with more than 100,000 reads in the first week. Over the next couple of years, we reported on two other prominent examples of treatment in Norway that fit into this medication-free category: one was the Hurdalsjøen Recovery Center, a private hospital that had opened in 2015 outside of Oslo, and the other was basal exposure therapy (BET), which offered an in-patient service at Blakstad Psychiatric Hospital that regularly helped chronic patients taper from their medications.

These initiatives made for a heady time, and they attracted the attention of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Health at that time, Dainius Pūras. Both the WHO, under the leadership of Michelle Funk, and Pūras called for a radical paradigm shift in mental health care, away from the biological model and toward a human rights model that honored the right of psychiatric patients to make choices about the care they wanted to receive, and the three “medication-free” efforts in Norway were seen as pioneers in providing such treatment.

Høie had issued his directive in response to years of lobbying by a fellowship of user groups in Norway, and thus it was a grassroots initiative, rather than one that Norwegian psychiatry, as an institution, had set in motion. Instead, from the outset, leaders in Norwegian psychiatry were vocal in their opposition, arguing that it was malpractice to not prescribe antipsychotics to psychotic patients and characterizing it as an “antipsychiatry” initiative that would harm patients.

Although all four health districts in Norway did comply, to some degree, with the Health Minister’s directive, setting aside at least a few beds for medication-free treatment, these beds were mostly reserved for patients without a psychotic diagnosis, and this institutional opposition to the initiative never faded away. And now the “door to a revolution” is swinging shut.

The Hurdalsjøen Recovery Center closed in early 2023 after a new government decreed that public funds would no longer be used to pay for patients receiving care at a private hospital. Last October, the University of North Norway Hospital, which runs Asgård Hospital, announced a plan to close the six-bed “medication-free” ward and instead rely on “consultants” to support drug-free treatment services at outpatient clinics throughout the region. This past June, the Vestre Viken Hospital Trust, which operates Blakstad Psychiatric Hospital, announced plans that would close the inpatient BET service.

This last announcement was particularly disheartening and, in many ways, surprising, as the WHO, in a 2021 document that told of model programs in the world that best embodied a human rights approach to psychiatric care, cited BET as one of three in-hospital programs to be lauded, and it was the only Norwegian program to be so praised by WHO. Høie wrote proudly of this acclaim, which Vestre Viken Hospital Trust still features on its website.

There is one other ward in Norway’s public health system, at Nedre Romerike, that has been providing “medication-free” services to psychotic patients, and just this week, We Shall Overcome, a psychiatric survivor group at the forefront of this effort to provide such care, learned that it too is scheduled to be closed.

“The last year has been a total blow for the medication-free initiative in Norway,” said Mette Ellingsdalen, a leader at We Shall Overcome. “Everything that has been achieved has been threatened, and even though we still fight, it is a demonstration of where the real power lies in the mental health system. When Lake Hurdal closed we lost the majority of medication-free inpatient places. If BET Blakstad and Nedre Romerike DPS now are closed, we are left with the possibility of a few beds in Tromsø. In harsh numbers, this is a tragic outcome after twelve years of hard work.”

Beacons of Hope

Asgård Medication-Free Ward

While BET is a service that was introduced by psychologist Didrik Heggdal in 2000, and thus not specifically a creation of the medication-free initiative, the six-bed “medication-free” ward in Tromsø, under the direction of psychiatrist Magnus Hald, was the first in Norway to open in response to Høie’s directive. It quickly became a visible example of possible wholesale change in psychiatry, and particularly so since it involved providing psychotic patients with the opportunity to choose whether they wanted to take antipsychotic medication, or, if they were on such medication before coming to the ward, to taper from the medication.

Asgård Psychiatric Hospital in Tromsø

Asgård Psychiatric Hospital in Tromsø

This patient choice ran directly counter to the disease model of care that is dominant in mental hospitals throughout the developed world, and if the ward could be run successfully, it would serve as a “proof of concept” that told of a better way, with patient choice regarding medications a central feature of the care. In a 2019 interview with Mad in America, Hald summed up their experience to that point.

Of the 50 or so patients who had been treated on the medication-free ward, more than half had chosen to not take neuroleptics while hospitalized. Contrary to what one might expect, Hald said, many who eschewed neuroleptics “didn’t seem to have psychotic symptoms” while on the ward. The others in this non-neuroleptic group, while psychotic at times, “are finding new ways to deal with the symptoms.”

The staff, Hald added, had seen the benefit that can come from patients getting down to lower doses or off the drugs altogether. The patients “often report that when they taper, they get problems back, but they find new ways to deal with them,” he said. “These people have a very strong feeling about getting their emotions back, and this is also experienced by their families. One woman told us, ‘I thought I lost my husband four years ago, and now he’s back.’”

Early on, there were two or three patients on the medication-free ward who were so challenging that they had to be transferred to the acute wards. But that hadn’t happened in recent times, Hald said, and during the ward’s three years of operation, no staff member had been assaulted, and none of their patients had committed suicide, including following discharge.

“We have been able to help some patients, and we have been able to address this question of how drugs are being used, getting this on the agenda,” Hald said. “That might be the most important thing we have achieved, is to be part of a movement, nationally and internationally, for this development.”

Magnus Hald speaking at a conference in Iceland

Magnus Hald speaking at a conference in Iceland

That was the status of the Tromsø ward in 2019. The six-bed ward was proving that it was possible for a psychiatric hospital to provide “medication-free” treatment, and that many patients would be thankful for this type of care. Indeed, a 2019 survey of 100 patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Norway found that 52% stated that they “would have wanted drug-free treatment if it existed.”

In October of 2023, when the University of North Norway (UNN) proposed shutting the in-patient “medication-free ward” at Asgård, it didn’t state that that it was doing so because of any complaint about the quality of care or poor patient outcomes, but rather to free up space for general care. The proposal to provide medication-free support in outpatient settings was presented as a way to preserve, at least to a small degree, this type of care.

In a letter dated October 29, the user organizations, led by We Shall Overcome, vigorously protested this proposal. They wrote:

“The drug-free program at UNN has been in operation for almost seven years. During this period, the service has built up a large competence base in drug-free services and special expertise in the responsible tapering of psychotropic drugs. The inpatient unit is a unique research arena and maintaining such an inpatient unit is important for further knowledge development in the area. Any establishment of a drug-free consultation team requires that the team is supported by a skilled competent environment, and should be anchored in such a drug-free inpatient unit.

“The proposal to convert the drug-free inpatient services into a consultation team is not justified by deficiencies in the service or lack of demand, but because the aim is to free up resources for other drug-controlled services. The proposal appears to be poorly thought out in relation to the national guidelines for drug-free treatment services. WSO believes that the proposal will in practice lead to the closure of drug-free services at UNN, which will have major negative consequences for users. At the same time, it is likely that the professional community at the drug-free inpatient unit will cease and the knowledge gained will be lost if it is converted to a consultation team.”

At this time, the fate of the medication-free ward at Tromsø is still in limbo. Mad in Norway, an affiliate site of Mad in America, has served as a media forum for protests against the closure, and it now appears that the protests may stave off its closure, with at least a few beds reserved for “medication-free” treatment.

Hurdalsjøen Recovery Center

The six-bed ward at the Asgård is embedded within a psychiatric hospital where traditional drug-centered care is the norm, and thus it provided a small “sample size” of what might be possible. The Hurdalsjøen Recovery Center was a residential facility, licensed as a psychiatric hospital, entirely devoted to that practice. As such, it served as a “large scale” example of what might be possible with medication-free treatment. Rather than set aside a few beds within a traditional hospital for medication-free treatment, Hurdalsjøen told of the possibility that this could become the standard of care.

The founder of Hurdalsjøen, Ole Andreas Underland, had spent years working in mental hospitals. He began working at Dikemark Psychiatric Hospital in Asker at age 18, and after he got his training as a psychiatric nurse, he rose to chief of staff of the hospital’s maximum-security unit, holding that position from 1988 to 1993. He subsequently started a private company that provided housing to people with mental and behavioral difficulties. That entrepreneurial venture, which he eventually sold, taught him that “if you give people proper housing, they can live a good life with support.”

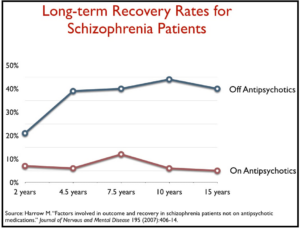

His decision to create a “medication-free” facility arose in 2013, when Jan-Magne Sørensen, the leader of the user group White Eagle, put up a slide at a conference telling of how, in the long-term study of schizophrenia outcomes by Martin Harrow, the recovery rate for those who had stopped taking antipsychotics was eight times higher than for those who continued taking the drugs. By that time, the user groups were lobbying the Health Ministry to provide psychiatric patients with a “medication-free” option, and even before Høie had issued his directive, Underland, on April 1, 2015, opened Hurdalsjøen.

Underland had solicited counsel from user groups to design the treatment program at Hurdalsjøen, and as such it was a place that reflected much of their vision for what an inpatient psychiatric center should be like. In addition to the “medication-free” option, the user groups requested that the facility provide good nutrition, the chance to be out in nature, and opportunities for exercise, relaxing and pursuit of creative endeavors. Half of the staff comprised people with “lived experience” as psychiatric patients.

“The treatment we have used since the 1950s has been medication, and it has been proven wrong,” Underland said in a 2019 presentation. “We spend more and more money on medication, and yet there is the continued growth of mental disorders. Relying on medication obviously doesn’t work.”

In order to come to Hurdalsjøen, most patients had to get a referral from their psychiatrists in the public health system. As a result, most who came here were chronic patients who had experienced years of treatment within the conventional system, where they had been heavily medicated, suffered repeated hospitalizations, and been forcibly treated.

The center’s first patient was 31-year-old Tonje Finsås, who arrived at Hurdalsjøen with prescriptions for 31 medications, including three antipsychotics, and a record of 220 hospitalizations over the previous two decades. When I visited in 2019, she had tapered down to two medications, was living independently in a nearby village, and was working half-time for the recovery center, helping to run its activities room, where patients could go to write poetry, knit, or do other such activities. Soon she was to begin working full-time as a “recovery pilot”, drawing on her experiences to help guide newly arrived patients as they moved down this new therapeutic path.

“My story shows it is possible to get better,” she told me when I visited in 2019. “It is possible to get back out there. Yes, I am high and low still, but I control it, I know what triggers it, and I know what to do . . . Without [this place], I wouldn’t be alive today.”

During my visit, I met several others who, like Finsås, had initially come to Hurdalsjøen as patients and were now working as recovery pilots. The food was excellent, staff and patients ate together at long wooden tables in a dining room that overlooked beautiful Lake Hurdal, and patients moved freely about the premises. One group returned to the dining room one day after having gone shopping in a nearby town.

The stories the patients told to me were much the same as I had heard in Tromsø. They had fared poorly in the conventional system, but now—with this option for medication-free treatment or support for tapering from the medications—they were regaining a sense of hope, and a belief that they weren’t doomed to be “mental patients” the rest of their lives. They spoke too of the emotional difficulties they continued to struggle with, but, they said, this care was providing them with a new path forward.

“We have made our choice,” Underland said during that visit. “This is going to be the most important psychiatric hospital that is making this revolution happen. We will show it can be done, and then the revolution will have to happen.”

At that time, the future of Hurdalsjøen seemed bright. The recovery center was becoming better known, the number of Norwegian patients petitioning to come here was increasing, and from 2020 to 2022 the 60-bed facility was regularly full. Finsås’ story of recovery became well-known in Norway, and the “biggest television station” in Norway” had aired a favorable documentary of Hurdalsjøen, depicting it as an example “of how a psychiatric hospital could be,” Underland said in a 2023 interview. A steady stream of international visitors came to visit, and under the Conservative government, which was in power from 2013 to 2021, the Norwegian Health System paid for the patient care at Hurdalsjøen, even though it was a private hospital.

By the end of 2022, 650 patients had been treated there, and in a survey of former patients, 80% stated that were satisfied, or “very satisfied” with the treatment. Seventy percent said they had wanted to stop taking psychiatric drugs or taper down to lower doses.

Ole Andreas Underland

Ole Andreas Underland

However, in 2022, the Labor Party came to power in Norway, and it declared that public monies would not be paid to private institutions, a policy that, once implemented, cut off the flow of new patients to Hurdalsjøen. By the end of that year, the facility was only half full. A Norwegian newspaper also published several articles sharply critical of the care at Hurdalsjøen, and whereas an earlier newspaper account quoted a patient who said this place “had saved his life,” this one focused on the fact that one of their patients had committed suicide.

As a private hospital, Hurdalsjøen did have financial struggles, as it was operating at a substantial deficit, and Underland and his staff had also learned how difficult tapering from psychiatric medications could be, which appeared to be a source of dissatisfaction from the 20% unhappy with the care.

“Eighty percent of these patients meet their personal goals of reducing or phasing out pharmaceuticals altogether,” Underland said. “But phasing out drugs is very demanding for many, and it has to be customized because some patients will respond with quite heavy side effects even if the dosage is taken down very little. We see that especially on antidepressants that they are very, very tough to reduce for some patients, but some other patients can reduce without having any problems at all.”

By that time, in early 2023, the closure of Hurdalsjøen was imminent. Underland organized a conference in a last-ditch effort to save the facility, hoping that it would encourage the Labor Government to sign a contract that would provide government payment for patients who wanted to come there. Speakers included Michelle Funk from the World Health Organization (via zoom), Dainius Pūras, the former UN Special Rapporteur for Health, psychologist Didrik Heggdal (the developer of BET), a former patient at Hurdalsjøen, a staff member, and a leader from the user groups. The overriding theme of the conference was that the WHO, the United Nations, and others were advocating for a “paradigm shift” at a global level in psychiatric care, and the medication-free initiative in Norway was a model for such change. The Tromsø ward, Hurdalsjøen, and BET were presented as evidence that it was possible to provide such treatment and do so with success.

The March conference attracted an audience of several hundred people, but Underland was unable to secure a contract with the Labor Government to pay for patients at the facility and it closed soon thereafter. During the conference I did pay a final visit to Hurdalsjøen which formed a lasting memory of the place. In a living room area, a small group of patients were gathered around a fireplace, and they were laughing about how earlier that day, several had climbed down a ladder into a hole cut in the thick ice of Lake Hurdal, and—surmounting their fears—had taken a quick dip in the ice-cold water.

That was a tableau that did speak of a psychiatric hospital of a different kind.

Basal Exposure Therapy

The Asgård ward and Hurdalsjøen provided what might be described as “case study” evidence of patient outcomes with “medication-free” treatment, but neither had been operating long enough to conduct a proper study of long-term outcomes, detailing how their patients were doing in comparison with patients treated within conventional care settings. However, the BET program at Blakstad has been operating since 2000, and research has shown that it can give chronic patients a new lease on life.

The patients admitted into the program typically have low functioning scores, numerous hospital admissions, and long-term use of psychiatric drugs (including polypharmacy). Most are described as “treatment resistant” when they enter the program, with BET seen as giving them a “last chance” at recovering from their serious difficulties.

The conception with BET is that serious mental disorders “are sustained by avoidance behavior.” Chronic patients avoid situations or environments that pose a risk of “existential catastrophe,” fearing that this can lead to their disintegration, or their “being engulfed by total emptiness or stuck in eternal pain.” Thus, serious mental disorders are treated as phobic conditions, irrespective of formal diagnoses, and the therapy is designed to expose them to the very conditions that stir their anxiety. Although this exposure may initially trigger increased anxiety, repeated exposures will reveal to the patients that they can survive such experiences without disintegrating and that the existential threat to their being “is not real.” This becomes the path to recovery.

As part of this treatment, patients are regularly tapered down to lower doses of psychiatric medications or supported to get off the drugs entirely. Psychiatric drugs are thought to hinder the recovery process because they are designed to suppress unwanted internal experiences, and yet it is precisely that internal experience that is needed to help patients get past their fears of existential catastrophes.

In 2018, Heggdal and colleagues published a study of the first 36 patients who had been treated with BET. They were able to interview or find up-to-date electronic records for 33 of the 36, with these patients having been discharged, on average, five years earlier.

The composite outcomes for the BET patients were quite good, considering that they had been considered “treatment resistant” and were doomed to be chronically ill when they first came to the BET program. The best results were seen in the 16 of the 33 that were off all psychiatric drugs. Compared to the 17 still talking medication, they had much higher “global assessment of functioning” scores, much lower re-hospitalization rates since discharge from the basal exposure program, and much higher “full-time” employment rates (56% versus 6%). Seven of the 16 in the drug-free group had “fully recovered,” while none of the 17 still using psychiatric drugs achieved this best outcome.

The researchers concluded: “Former patients who had undergone basal exposure therapy and were drug-free at follow-up at least two years after discharge had significantly better psychosocial functioning and showed a more positive development in terms of their ability to work and live at home unaided than those who continued to use psychotropic drugs. Fewer of those who were drug-free had been readmitted or remained in contact with mental healthcare institutions.”

I visited Blakstad in March 2023, during my trip to speak at Underland’s conference, and the BET patients told stories similar to the ones told by patients at Asgård and Hurdalsjøen. Most had experienced what they described as the horrors of forced treatment, and they had spent years cycling in and out of hospitals while being prescribed an ever-increasing array of psychiatric drugs that worsened their functional capacities. At BET, which is located in a house-like setting, they were regaining an emotional strength and resolve to move forward in a new manner. The care that had destroyed their lives was replaced by treatment that was giving hope that they could get their lives back.

One of the patients who spoke to me was a 30-year-old woman, Caroline, who told of suffering trauma as a child, such that she had first contact with the psychiatric system when she was only 10 years old. There she got the message that “emotions were not allowed.” She was first admitted to a psychiatric hospital when she was 15, and for the next ten years she was prescribed dozens of psychiatric drugs—antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines—and cycled in an out of psychiatric hospitals, with many suicide attempts and suffering intense physical pain from the dystonia cause by the drugs.

She first came to the BET program in 2019, and is known in the program as one of their “sequential” patients, with healing understood to be an ongoing process that can take years. She has periodically come back to the BET inpatient facility for stays of one to two months, while continuing to receive BET-informed care at outpatient clinics the rest of the year.

Over this time, she has learned to confront her many existential fears, and has slowly tapered from her polypharmacy regimen, although this drug-withdrawal effort remains incomplete. “I have just one goal ,and that is to not merely exist,” she told me. “It is to live with everything that being alive involves, with every emotion. I want to be able to experience these emotions, and be a whole human being.”

In June, the BET staff learned that their service may be closed. The Vestre Viken Hospital Trust is in the process of revamping its psychiatric services, which may involve transferring services from Blakstad to a new central hospital in Drammen, and thus this inpatient service at Blakstad would end. Much as the threatened closure of the Tromsø ward stirred a public protest, so too did this news.

Two former service users have put up a petition on change.org seeking international support for maintaining this inpatient service. One of the two women, Vibeke Normann, had once been deemed treatment-resistant and “subjected to much coercion,” but then recovered after the BET treatment, and is now a cancer nurse.

In their petition, Normann and Vivian Kihle Karlsbakk wrote:

“We demand that Vestre Viken halts the closure of the Basal Exposure (BET) mental health inpatient treatment unit at Blakstad Hospital. Closing these beds would be contrary to international requirements and guidelines for developing services based on human rights, recovery, and humanism. The BET unit is highlighted by WHO, the Council of Europe, and the UN as an example of the future of mental health services, demonstrating how to achieve good results through increased voluntariness and reduced use of coercion and medication. This approach addresses many of the challenges we face in the field of mental health today. Closing the unit at Blakstad Hospital would be a significant setback for mental health services in Norway.”

The Vestre Viken Trust is expected to make a final decision about the closure of the BET unit in August.

International Praise for the Three Programs

Together, these three efforts—the ward in Asgård hospital, Hurdalsjøen, and the BET program—told of a country that was charting a new path for psychiatry, one that offered patients, including those with the most “serious” disorders, the opportunity to be treated in inpatient settings without the use of psychiatric medications if they so chose, and in environments free of coercion.

This latter element—an environment free of coercion—is consistent with the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons With Disability (CRPD), which called for an end to forced treatment. In October 2023, the World Health Organization and the United Nations Office of the Commissioner on Human Rights jointly published a lengthy document, Mental Health, Human Rights, and Legislation, that emphasized the need for countries to comply with that directive. The authors wrote:

“From a human rights perspective, coercive practices in mental health care contradict international human rights law, including the CRPD. They conflict with the right to equal recognition before the law, and protection under the law, through the denial of the individual’s legal capacity. Coercive practices violate a person’s right to liberty and security, which is a fundamental human right. They also contradict the right to free and informed consent and, more generally, the right to health.

“Coercion can inflict severe pain and suffering on a person, and have long-lasting physical and mental health consequences which can impede recovery and lead to substantial trauma and even death. Moreover, the right to independent living and inclusion in the community is violated when coercive practices result in institutionalization or any other form of marginalization.

“Coercive practices in mental health care violate the right to be protected from torture or cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment, which is a non-derogable right.”

Both the World Health Organization and the former United Nations Special Rapporteur for Health, Dainius Pūras, have pointed to the Norwegian initiatives as models for a needed paradigm shift, at a global level, in psychiatric care. In particular, the absence of coercion is central to a human rights approach to mental health, and the WHO, in a 2021 document titled “Guidance on Community Mental Health Services: Promoting Person-Centred and Rights-Based Approaches,” cited BET as a model for reform.

In its review, the WHO praised BET for “requiring people to take responsibility for their own choices,” for helping people “taper from psychiatric medications,” for its “non-coercive practices, “and for helping people “find housing, return to work or school, or connect with peer networks or similar services in the community.”

Here is what the WHO wrote regarding an “evaluation” of its services:

“A growing body of evidence demonstrates that the use of coercion in treatment can be reduced by as much as 97% and that service users’ quality of life and psychological and psychosocial functioning can be significantly improved. A retrospective study from 2017 found individuals who used the [BET] service had fewer admissions to psychiatric and general hospitals in the 12-month period after discharge from BET, compared with the 12-month period before admission.

“One qualitative study of service users at the BET Unit found that participants displayed less symptoms, a significantly improved level of functioning and re-established connections with their families. Some even started their own families, and were engaged in education or work. Some stopped using medication altogether.

“Several users of the BET service have participated in qualitative studies and reported experiencing a normal life. As one service user recounts, I had been told ‘You have a serious mental disorder that can’t be cured. You have to rely on medicine for the rest of your life.’ And so, I went to the BET Unit, and got discharged without any diagnosis, with no medication, without anything.”

The WHO also observed that the daily per-patient cost in the BET unit was 30% to 40% less than in other mental health units at the Vestre Viken Hospital Trust. The Council of Europe similarly praised BET in its 2021 compendium report “Good Practices in the Council of Europe to Promote Voluntary Measures in Mental Health.”

Even today, the Vestre Viken Health Trust website features the praise that Brent Høie, in his capacity of Minister of Health and Care Services, heaped on BET following its selection as a model program by the WHO. Here are excerpts from his talk:

“Congratulations to the BET section at Blakstad Hospital! You are leading the way in the development of mental health care based on human rights and where the patient’s needs and wishes are listened to and emphasized. It’s great that the WHO is highlighting the work you have done.

“I’m particularly pleased that the WHO recognizes the work that you and Norway have done to implement drug-free treatment for patients in mental health care. Drug-free treatment allows people with serious mental illnesses to live a life without major side effects of medication. It contributes to increasing coping and makes active lives and social participation more possible.

“I hope that [your] work inspires other countries to adopt drug-free services and to emphasize human rights in the treatment of people with mental illness.”

Thus, only a few years ago, Norway was providing a model for a revolutionary change in psychiatric care that other countries could follow. The three medication-free programs provided patients with a choice regarding the use of psychiatric medications, didn’t rely on coercive practices, were supported by user groups, and—according to patient accounts and the limited research available—were producing good outcomes.

Yet, in spite of the “success” of these initiatives, one has shut down completely, and the other two are threatened with being downgraded into “outpatient” care, which of course would mean that they no longer presented any real model of reform for other countries to follow. There are small BET programs in two other Norwegian hospitals, but Blakstad is the center for this service, and its closure at Blakstad would remove this model of care from international public consciousness.

The Power of Institutions

This revolution in psychiatric care in Norway, which was launched when Høie issued his directive for the four health districts in Norway to provide “medication-free” treatment, always occupied a tenuous position in Norway. Mainstream Norwegian psychiatry is very biologically oriented, and leaders in Norwegian psychiatry have opposed the medication-free initiative, and often fervently so.

It is easy to understand why they would be so opposed. The Health Minister’s mandate served as a rebuke to the treatments they oversaw in the country’s mental hospitals, where coercion is common and psychiatric drugs, often prescribed in abundance, are a first-line treatment.

As such, the international interest and praise for the “medication-free” initiatives, which included praise from the World Health Organization and the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Health, could be expected to heighten this opposition within Norwegian psychiatry. The international lauding of the initiatives occurred against a public backdrop that told of how forced treatment was commonplace in Norway, with patients telling of seclusion, being placed in restraints, and heavily drugged in conventional hospital settings.

That was not a public narrative that mainstream psychiatry in Norway could embrace, but rather one it was primed to contest.

“One of the main justifications for a treatment regimen that harms so many of its patients is that there are no viable alternatives,” Ellingsdalen said. ”As a result any place that demonstrates that it is possible to help people without infringing on their human rights is perceived as a fundamental threat to the system, rather than places to learn from.”

She added: “The stated reason for all the medication-free units has been that there is a need for re-organizing services and for economic reasons, and not for ideological reasons or connected to results. But even so it is naïve not to think it is connected with the opposition from the traditional mental health system. In the last year we have seen the Norwegian Psychiatric Association ramp up their public defense for biomedical psychiatry. While the opposition against the medication-free wards from many psychiatrists has been there all the time, it has now become a more public stance from the psychiatric association. We also have a government that has stated it’s ‘time to listen to the mental health professionals.’”

And Yet, the Protests Persist

The closure of Hurdalsjøen, together with proposals for closing inpatient “medication-free” services in Tromsø, Blakstad, and Nedre Romerik, tell of a potential “revolution” in psychiatry, given birth eight years ago, that is nearing an end. The decree from the Health Minister that ordered the four health districts to offer “medication-free” treatment, providing even psychotic patients with that choice, represented a potential systemic change to psychiatric care in hospital settings, and that is why it attracted international attention and, when observers came to visit these settings, international praise. The praise told of how giving patients choice regarding the use of medications could be done in hospital settings, even with psychotic patients. And while tiny pockets of such care may be preserved within the Norwegian system, the systemic challenge that was present when Høie issued the governmental decree is no longer present, and in that sense, the “revolution” has been put down. The institutional power present in hospital psychiatry has emerged triumphant.

Yet, each planned closure has generated protests, with the voices of protest not relegated solely to user groups. Mad in Norway launched five years ago, which is led by an editorial team that brings together mental health professionals and user activists, and it has a large readership for a country of 5.5 million. The voices of protest are seeking to blow fresh air on the dying embers of this “revolution” in care.

“The protest (against Tromsø’s closing) came together from many groups, patients, mental health professionals, human-rights defenders,” Ellingsdalen said. “The support for medication-free treatment has deeper and wider roots than only from smaller activist groups like We Shall Overcome. Even though the resistance towards change has somehow strengthened in Norway, the call for a paradigm-shift also continues to grow, because it is a just cause based in human rights, science and humanism.”