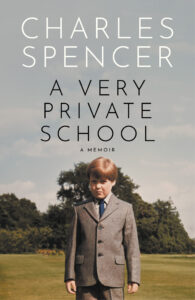

On 10 March, the Mail on Sunday put Charles Spencer’s story about being sexually abused at boarding school on its front page. Spencer is the brother of the late Diana, Princess of Wales. Inside the paper were extracts from Spencer’s book, A Very Private School, about his time at Maidwell Hall, where he boarded from eight to 13. When he was 11, a female assistant matron who was 19 or 20, and who was already abusing boys in her care, began abusing him. These children were motherless, unprotected, desperate for love, and unable to acknowledge that they were being exploited. Fifty years later, Spencer has broken the silence.

Maidwell Hall, which still exists, stated that it was ‘difficult to read about practices which were, sadly, sometimes believed to be normal and acceptable at that time. Almost every facet of school life has evolved significantly since the 1970s. At the heart of the changes is the safeguarding of children and promotion of their welfare.’

At Maidwell, in addition to sexual abuse, Spencer and his peers were subjected to brutal beatings by the headmaster. While corporal punishment was legal, and may have been believed to be ‘normal and acceptable’ in the 1970s, the sexual abuse of an 11-year-old boy by a 19-year-old woman was not. While it may have happened in some schools, and while some adults who knew about it ignored or endorsed it, this does not mean it was believed to be acceptable. That it took place at Maidwell was due to institutional sadism and neglect. If parents who sent their sons to the school in 1974 had been told that such abuse was a normal and acceptable part of the education their children were to receive, all but the cruellest of parents, I wager, would have removed their sons immediately. Maidwell in the 1970s was not fit for purpose. Parents trusted it to bring up their boys; instead, it broke them.

As for the latter part, while Maidwell claims that ‘almost every facet of school life has evolved since the 1970s,’ the basic structure of boarding institutions remains the same. At the beginning of term, children leave their homes and families to enter the school, where they sleep in a dormitory shared with other children. They eat every meal at school; they spend evenings and weekends at school; they are subject, round the clock, to the regime and routines of the school. (Maidwell now accepts ‘flexi-boarders’, who spend two or three weeknights at school, but half its boarders still board full-time.) As for the ‘safeguarding of children and the promotion of their welfare’, psychiatrists and psychotherapists have spoken out for years about the risk of psychological harm in separating an eight-year-old from their parents.

Meanwhile, alleged abusers have recently been present in other boarding schools. In 2023, a teacher at the boarding school I was sent to was banned from teaching. Three years earlier, the school had received a report of him making sexual advances towards a pupil in the 1990s. The teacher retired shortly after the school received the allegations, after four decades working there. Institutions full of parentless children far from home attract these kind of people.

In A Very Private School, Spencer explains how being sent to boarding school silences children. ‘I felt I’d been sent away from home because I’d somehow fallen short as a son,’ he writes. ‘The last thing I wanted was to make the situation worse by being difficult, or questioning, since that might bring about even harsher rejection.’ (His older sister Diana, he wrote, ‘had countered her first-day despair on reaching boarding school with the heroic challenge: ‘If you loved me, you wouldn’t leave me here’.’)

I was sent to boarding school at thirteen. I did not want to go. A week before term was due to begin, I told my mother, yet again, that I wanted to stay home and go to day school. I knew in my gut that I must not leave. I was too young and I was terrified. But she refused my plea. The rejection was so frightening that even before I had begun at boarding school, part of me shut down. I dared not ask to be kept home again; I could not face rejection from my mother again.

After my parents left me at the school, I felt immediately that my entire life up to that point had been a deception. I thought my parents loved me and wanted me; I thought I belonged to a family; I thought I would always have a home. But I had been left in an institution, sharing a tiny dormitory with five other girls, with whom I had nothing in common. The school was two-and-a-half hours’ drive from my house, in a different county I knew nothing about. The only way to survive such abandonment is to kill yourself inside. The part that feels, that loves, that misses home and family and friends, must die.

Spencer writes: ‘I am certain that some things died for me between my eighth and 13th birthdays…Innocence, trust, joy – all were trampled on and diminished in that outdated, snobbish, vicious little world that English high society constructed and endorsed, handed over to the care of people who could be very dangerous indeed.’

He expresses shame at his own complicity, a shame that others traumatised by boarding school may understand. ‘It amazes me still that I – always a stubborn child – meekly succumbed to the misery of the bleak path chosen for me. It just didn’t occur to me to rebel. My disappointment in myself for this unconditional surrender has only grown as I’ve aged.’ The psychoanalyst Adam Phillips calls complicity ‘delegated bullying’. When you’re made complicit in your own abandonment, you become your own destroyer. Spencer describes cutting his arm at school with a penknife, and making himself sick in his chamber-pot at night. In the morning, he showed his ‘feeble offering’ to the senior matron, who looked at him ‘contemptuously’ and told him to wash the pot. This continued for years. ‘She never showed an iota of concern,’ he writes. ‘It’s obvious to me now that making myself sick was a desperate attempt to get somebody adult to show me warmth and sympathy. It was an emotional cry for help and an effort to exert an element of control over a life that was so out of my control.’

At boarding school, I too began having problems with food. In the evenings, trapped in my dormitory, bored and desperate for home, I ate. Eating as ‘a response to conflict situations may be viewed in two ways,’ writes the psychoanalyst Rollo May. ‘First it may be a somatic expression of the psychologically repressed needs of the organism to be cared for. The person endeavours to resolve anxiety and hostility and gain security through eating. Second, it may represent a form of aggression and hostility toward those who deny the comfort and solace desired.’ Or as the psychiatrist Frieda Fromm-Reichmann puts it, ‘the attempt to counteract loneliness by overeating serves at the same time as a means of getting even with the significant people in the environment, whom the threatened person holds responsible for his loneliness’. Overeating, in other words, can be a sign of a desperate need for care, and at the same time fury at the absent carer.

When I returned from school for the Christmas holidays, my house was no longer my home. I had yearned for it for months, and yet being back there was too painful; it reminded me of all that I had lost. I had no words to communicate my pain; to be unhappy at school would be to fail, to be needy, to be too desperate for a mother who didn’t need me. Instead, I told my mother I was too fat. My thighs were too large; I needed to lose weight. I hoped, I think, that in hearing my relentless self-attack, she would realise something was wrong. But she didn’t. One afternoon, as my adult half-sister and I were watching TV, my mother asked if we wanted hot chocolate.

‘Yes please,’ my sister said.

‘Yes please,’ I said.

‘If you’re so worried about your weight, you shouldn’t be having hot chocolate,’ my sister said.

She was right. I called back to my mother that I didn’t want one. In fact, I shouldn’t be eating at all.

I needed comfort from my mother; she couldn’t give it, but she could offer hot chocolate. I accepted it, as a substitute for emotional care. But then my sister pointed out that I shouldn’t have the hot chocolate. I should deny myself it, and in doing so, deny myself comfort. And so I did, absolutely. I decided to go on a crash diet. When I returned to school for the Easter term, I ate only fruit for days.

Back at home in the Easter holidays, I hoped that my mother, father or three adult half-siblings would notice my drastic weight loss, my absence from meals, or, when I didn’t manage to disappear from the kitchen in time, my only accepting green vegetables. ‘Refusal,’ Marina Benjamin writes, ‘is the last recourse of the powerless’. For a period, I ate only All-Bran, snatching it in handfuls from the box throughout the day. My mother finally noticed, but she just snapped at me to stop. The pain my psyche could not bear was instead lived out through my body, through starving and stuffing, in a family that was blind.

Having been forced into self-reliance at boarding school, it became dangerous to articulate my need for care. As Spencer puts it, ‘I ensured no vulnerabilities could be left on show’. But one afternoon, at home during the Easter holidays of my second year, I couldn’t hide my despair. All my schoolmates lived a hundred miles away. My two friends who went to day school had new friends, none of whom I knew. I was no longer part of any local clubs; I had no one to play with. All powers of self-direction had died, shortly after I had been locked up in a school where free time was controlled and punctuated with roll calls. Wretched and lost, I sat on the kitchen floor and cried. I had no answers for myself; I desperately needed help. My mother began talking to me. Then my adult half-brother walked in. He filled a glass from the cold tap and took a long draught.

‘What’s she whining about?’ he asked my mother. He liked to talk about me in the third person while I was in the room; he thought it was funny.

My mother frowned. Nothing was done; no help was given. When the summer term began, I was sent back to school.

Three years later, I was home for the holidays again, in despair again. I had been rejected from the university I wanted to attend. A psychologist was giving me cognitive behavioural therapy, and his instructions to change my thoughts, to think in less faulty and distorted ways, were decoupling the gears of my mind. A few weeks previously, I had finally told my mother I had eating problems, four years after they began. I needed support, belief and someone to listen. Once again, my older brother walked into the kitchen where I was talking to my mother. He saw me in distress.

‘Tell her to pull her socks up,’ he told my mother.

‘But she has an eating disorder,’ my mother said.

He was twenty-nine. He had not been sent to boarding school. He had lived at home for all but the three years of his undergraduate degree, which he took at a university forty minutes’ drive from our house. He had not been exiled at thirteen; he did not know what it was like to lose a home, a mother, a self. And yet he policed every one of the few expressions of despair I betrayed. When I showed upset, vulnerability or need, he admonished me for weakness. My worst fear was confirmed; no one helped when I asked.

It didn’t matter that I was upset; I had no right to show distress. The only defence my mother had against my brother’s order to chastise me was that I had a psychiatric ‘disorder’. I warranted attention once I gained that label. In the years that followed diagnosis, I clung to it; only the ascription of ‘disorder’ permitted me care. It was a decade before I realised that it was destroying me. But it was the only way, in my family, that problems could be parsed.

In December 2022, I wrote an article about my own experience at boarding school. In the hours, days and weeks after it was published, people on the internet – whom I don’t know and had never met – wrote to me, expressing their sorrow about what had happened. Some of them had boarded too, and they shared their own accounts. It was one of the most extraordinary experiences of my life. For the first time, I had told my story, and it had been received. I had not been attacked or silenced; strangers showed me love. Some people told me that reading my essay enabled them to put into words, for the first time, what had happened to them. My writing, somehow, made more writing possible.

Three months after my essay was published, I went to an alumni drinks evening organised by my prep school. I was a day pupil at the school until I was thirteen, but for decades it has accepted boarders from eight. At the event, a 24-year-old alumnus told me he had recently found the first letter that he had written home after being sent to board at eight.

‘Dear Mummy’, he had written, ‘I feel you have abandoned me’.

After recounting this, the 24-year-old tipped his head back and laughed. My insides chilled. He began talking about how some boarding schools today offer ‘flexi-boarding’. He was against it.

‘If you’re in, you’re in,’ he said. ‘None of this half-half stuff.’

The chill rose up my throat. He had been abandoned at eight, so every other boarder should be entirely abandoned too.

The fact that Charles Spencer’s ordeal was on a front page is significant. Like me, his voice was taken away. His now has the platform it deserves, but after far, far too much harm was committed. His story will, I am sure, enable more people to share their own experience. He deserves enormous credit and respect for publishing it. The boarding school system is rotten; the stories of people who survived it are remarkable.

References

My essay: Charlotte Beale, ‘Boarding schools are bad for children. Why do they still exist?’, available here

Marina Benjamin, ‘Personal Growth’, Granta (2022)

Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, ‘Loneliness’, Psychiatry. 1959 Feb; 22(1):1-15, available here

Rollo May, The Meaning of Anxiety, (London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1950) p. 67

Adam Phillips, ‘Against Self-Criticism’, London Review of Books (2015)

Charles Spencer, A Very Private School (London: HarperCollins, 2024)

Resources

Books

Boarding School Syndrome: The psychological trauma of the ‘privileged’ child by Joy Schaverien, Routledge, 2015

Trauma, Abandonment and Privilege: A guide to therapeutic work with boarding school survivors by Nick Duffell and Thurstine Bassett, Routledge, 2016

The Making of Them: The British Attitude to Children and the Boarding School System by Nick Duffell, Lone Arrow Press, 2000

Wounded Leaders: British Elitism and the Entitlement Illusion by Nick Duffell, Lone Arrow Press, 2014

Articles

Revisiting Boarding School Syndrome: The Anatomy of Psychological Traumas and Sexual Abuse by Joy Schaverien, British Journal of Psychotherapy, Vol 13. Issue 4, Nov 2021

Working with Gay Boarding School Survivors by Marcus Gottlieb, Self & Society, Vol. 33 No. 3, 2006

Reflections of a Survivor by Thurstine Bassett

Wounded Leaders by Nick Duffell, Therapy Today, July 2014, Volume 25 Issue 6

Power Threat Meaning Framework: Overview, ‘Surviving separation, institutionalisation and privilege’ (p.70) by Lucy Johnstone, Mary Boyle et al. (British Psychological Society)

Oh yes, forgot to say, I am sharing this widely! Already others are responding positively. Thankyou again for what you have written.

Thankyou Charlotte. As an ex boarder and also survivor of lived experience, I echo your thoughts.