On the Mad in America podcast this week, we chat with author and educator Tanya Frank.

Tanya has worked as a college and university lecturer in the UK and taught middle school children, teens and elders in the US. She has also trained as a wildlife guide in California and has been an advocate for people with lived experience of psychosis. Tanya’s work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, and the Washington Post, as well as appearing in literary journals, including KCET Departures and Sinister Wisdom.

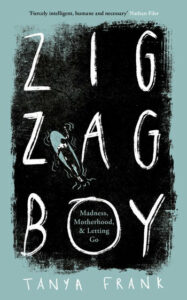

In this interview, we talk about Tanya’s recently released book entitled Zig-Zag Boy: Madness, Motherhood and Letting Go, which chronicles the experiences of her son Zach, who experienced psychosis as a 19-year-old. The book is a heartfelt and beautifully written account of dealing with mental distress and speaks movingly and honestly about the family’s struggles with broken healthcare systems in the US and the UK.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

James Moore: Tanya, welcome. Thank you so much for joining me today for the Mad in America Podcast. I’m thrilled that we can get to speak to you.

Tanya Frank: Thank you. I’m thrilled to be here. It’s an honour.

Moore: As mentioned in the introduction, you are a trained teacher and lecturer. You’ve been a wildlife guide in the US, known as a docent, and most recently, you’ve been an advocate for families with experiences of psychosis, but we’re here today to talk about your writing and in particular, your latest book entitled Zig-Zag Boy: Madness, Motherhood and Letting Go.

Could you give us a flavour of the book, what it is about, and what motivated you to write about your family’s experiences?

Frank: The book covers a 10-year span in my life and it’s the journey that I took with my son from the moment of his first altered state, which is often known within the medical model as psychosis, up until the end of the pandemic.

Frank: The book covers a 10-year span in my life and it’s the journey that I took with my son from the moment of his first altered state, which is often known within the medical model as psychosis, up until the end of the pandemic.

We travelled through America and the UK in search of answers and in search of treatment. We were trying to fix this thing for the longest time until the point that I realized that I need to try and grow into a sense of acceptance and ask different questions rather than just be led solely by the biomedical medical model which sees this as something rooted in the individual and something broken.

So, it intersperses this journey with my son through different treatments with an elephant seal colony where I worked as a docent. This was my time and my space away from this other world that was quite consuming. It gave me time to think and reinvent myself a little bit. It was completely off the grid. So, nobody could reach me, which was very difficult at first.

I think that the elephant seal was, like a lot of things in nature, a metaphor for what Zach was going through. So the mystery of one of the largest, deepest-diving marine mammals really reminded me in a lot of ways of the mystery of the brain. So much that couldn’t be understood, and when the elephant seals had to leave their pups, it gave me a lot of food for thought about how I might step away a little bit from what was going on with Zach, and what that meant.

Moore: Thank you, Tanya. The book is deeply affecting and beautifully written. If someone tried to get me to think previously about possible parallels between marine life and mental distress, I would have struggled, but your writing makes those connections seem so natural and meaningful.

Frank: Thank you.

Moore: So Zach had started to struggle with unusual experiences, and you talk in the book about the way that his diagnosis changed according to who he saw. That seemed to shake your confidence in the system. You used a brilliant phrase about your experience of the diagnosis process. You said, “It’s guesswork, trial and error. More like a game of spin the bottle than science.”

Could tell us more about what you were expecting from getting a diagnosis, how it worked out, and what you feel about it?

Frank: In the beginning, when Zach first went into the hospital, he came out with a diagnosis of psychosis NOS, where NOS stood for “Not Otherwise Specified,” which seemed vague to me. It made it hard to understand quite what it would have meant.

I did some research which led me to other terms and to look at the idea of psychosis, but it really did seem like a label used when the clinicians weren’t sure how to label something. They said that it could possibly be just one episode, and it might never happen again. They thought that it could be from marijuana use and if Zach could stop smoking, that it would diminish.

So, it really caused me a lot of time away from Zach being distracted by trying to understand what this label meant and how it would affect him and affect all of us rather than just being with him, and his distress. And then, of course, the label changed over time, and that was interesting because sometimes he would be classified as having schizophrenia or paranoid schizophrenia, or psychosis with depressive traits.

Schizo-affective disorder was one that seemed to stick for the longest, but even now, sometimes I notice on reports that clinicians write different things and that seems like either they disagree between themselves or that actually, it’s not as important, as long as it has “schizo,” or “schizoid,” or something of that kind of terminology within it, but it’s almost lumped into the same syndrome or disorder.

Moore: I think you are the only person that I have spoken with for this podcast who has experienced the mental health system on both sides of the Atlantic. When you were taking Zach in for treatment, did you find the approaches similar or very different?

Frank: I found them similar in some ways, but I found them different in other ways. In America, the health system is often insurance-based and there is a lot more private healthcare. So, people that are employed might have insurance through their employer, students have insurance through the university. If you are quite poor, if you are somebody who isn’t employed or doesn’t have insurance through employment, you have a different kind of insurance. You are insured through the state, and there are different treatment programs and different hospitals, depending on what kind of insurance you have. It was a very stark difference.

When Zach had insurance as a student, he was able to go to hospitals where they looked much cleaner and they weren’t as crowded. He had his own space and I could visit more often. I could sit by the side of his bed and go into a little cafeteria and have tea. So, it seemed, I guess, a little more humane.

In the hospitals when we did not have insurance, they felt much more like prison, even though I’ve never been inside an actual designated prison. It felt very prison-esque to me. I was never allowed to see where Zach was sleeping. We met in a kind of canteen where there were almost like, it felt like prison guards on duty that would stand and the visiting hours were much less, and even the medication was different.

In the private hospitals, you were able to have medication that was in pill form. In the hospitals that were run by the state, they were more often about giving depot injections and they would also turn people out very quickly. Often when they were in a worse state, to my mind, than when they went in.

In our case, when Zach was still very traumatized, they would do a depot injection and just release him. Some people would be put in a taxi and go to skid row or a homeless hostel. So, that felt quite different, in a way, to here, in the UK, where although Zach was discharged into homeless accommodation it was often like a bed and breakfast.

There are some similarities in terms of the reliance on drugs. I think that the UK is moving very quickly in a similar fashion to the US in terms of pharmaceuticals being the first line of defence, and also there are more private insurance and private hospitals that are springing up to deal with mental health when the NHS doesn’t have the funding or the capacity. So, I think there are similarities in that way.

Moore: When you are over here in the UK, there is a part of the book where one of the mental health team says to you, “Unfortunately, Zach might have to get much worse before we can help him,” and that’s such a terrible place to put people into, isn’t it? Zach is probably not quite well enough to live unsupported on his own, but they are deeming him not ill enough to need hospital treatment. That must have been a terrible place to be.

Frank: Yes, absolutely, it was so distressing because your loved one is so vulnerable that you are in a state of fear much of the time and especially for families that lack resources. I wasn’t homeless, I had enough money to be able to accommodate Zach and we weren’t facing some of the barriers that some people face.

Yet, even for us, it was excruciatingly difficult to know that to be helped, you had to be in a place where you were about to throw yourself off a bridge or be classified as dangerous to yourself or others to qualify for that support. And then, even when that support comes, it’s about how medicalized it is. There is not really a sense to talk about it or see it as a process, but rather at that point, it’s really about controlling somebody’s behaviour, and it’s all about averting risk.

So, it felt like there are these two ends of the spectrum. There are so many people waiting to even see someone to talk about their grief or their trauma or their distress at one end and they wait and wait. Then there is the other end of the spectrum for Zach and other families like ours, where the so-called illness is almost criminalized to the extent that somebody is locked away and warehoused, and it’s very difficult to move them back into the community, which is to my mind the place where people can heal or recover, or be with loved ones in a way that helps them most.

Moore: Thank you so much, Tanya. I’d like to ask about the complicated relationship that Zach had with his prescribed drugs. He was given antipsychotics but he seemed to struggle with them almost from the get-go. It must have been quite hard to think that he was going to be helped by them, and then he see him suffer the adverse effects. So, I hope it’s okay if I read a little bit of what you wrote in the book because it’s so powerful.

You say, “The pharmacist explains that the prescribed low starting dose of the psychiatric drugs is apparently the norm. There are instructions to increase slowly to avoid side effects. So, it surprises me when I wake the next day to find Zach perched on the edge of the couch with his knees bouncing up and down, his hands on them, trying to still his movements. His eyes twitch and his tongue flicks in and out like the bearded dragon he kept as a boy. He walks around the house for no reason other than his mind and body won’t let him be still.

“’I feel like there is something inside of me, trying to get out,’ he says, between lip-smacking bites. His distress makes my stomach lurch. I place my feet flat on the floor and brace myself to try and quell the effects of his jittery legs.”

That’s really tough to read and I would imagine, incredibly tough as a mother to see going on with your son. You write really well in the book about Zach’s relationship with his drugs and his thoughts about them, but I wondered how you felt about how the drugs were used and whether they were helpful for Zach.

Frank: It’s an interesting question and I think it’s a really emotive one around the drugs because of course there are people that feel that these drugs have saved them and saved their lives. So, I’m not talking for the entire population but definitely, for Zach, the drugs have never really helped him and in fact, they have always seemed to harm him.

He now has Parkinsonian tremors that are so extensive from high doses of antipsychotics that he often can’t sleep and it’s very distressing to see that. He also has metabolic syndrome, which is very common for people that have been on antipsychotics for any length of time. This is high blood sugar, fatty liver, and high blood pressure. There is a lot of excess weight because the drugs can cause carbohydrate cravings and also the metabolizing of food in a very different way to those of us that aren’t on those drugs.

In the beginning, I never realized that these drugs were so powerful and that if Zach refused them, he would often be labelled as non-compliant. Seen not as somebody who was just ill but as somebody who was quite deviant because he didn’t want to comply. And then when the drugs didn’t work, he was often labelled treatment-resistant but still given the drugs.

So, it was confusing to me that if something isn’t working and it’s harming somebody that there wasn’t any attempt to look at stopping or tapering or trying maybe some talk therapy. It’s very hard to find doctors who taper in a way that’s safe enough for somebody to be able to come off the medicine. The higher the dose and the longer somebody remains on it, the more difficult it can be to stop those drugs just because of the dependence, the physiological reliance, and the way that the drugs can change the brain.

In the beginning, I really trusted the doctors because why shouldn’t I? I was brought up to trust doctors and I thought that the medicine would be a cure. So, it shocked me and I remember a psychiatrist adamantly saying to us, “You have to keep on with these drugs. If you stop, you will end up in the hospital,” that was such a strong message and it made us frightened about having to go back to the hospital.

So, I would often try to force him, I was another coercive element in saying that we have to keep going. We have to trust the doctors. You have to take this medicine. I think in retrospect, I wish that I had given Zach and our family a chance to try some other options because I think once somebody is exposed to the kind of trauma and the kind of long-term drugging that Zach has experienced, it becomes much more complicated and much harder to find that place. I don’t know what you might call it, a baseline or return to some semblance of joy and autonomy as a human because I think it’s messier and you’re unpicking a lot more than when you first started with this human distress, this human thing that all of us as beings go through in our lifetimes.

Moore: Thank you for sharing that. It also struck me in reading the book that actually, Zach had incredible insight into the drugs that he was taking for his condition. At one point, he tells his girlfriend Savannah that when he takes his prescribed drugs, he feels numb inside. He feels dead and if he feels that, he may as well be dead. The experience of psychosis is at least one with feelings, as extreme as they are. He knows he is alive in that state.

That stuck with me because one of the things that befall people that sadly struggle with mental distress is at some point, they get labelled that they lack insight into their own condition. And yet, here is Zach with perfect insight into it. He feels either sedated and disconnected on the drugs, but when he is hearing voices or having his experiences, at least he knows he is in touch with the world.

Frank: Yes, absolutely. And there is a medicalized term for this lack of insight as well, “anosognosia.” People that believe in it espouse the notion that there is this lack of insight, and if only somebody could develop insight and take their medicine as prescribed that they would get better and live happily ever after.

I think my a-ha moment when I started questioning some of these ideas was when we met a psychologist in Northern California. It was some years into Zach’s journey and she had been given the same diagnosis as Zach. She also spoke about how she felt so numb, just like Zach did, that she was willing to end her life because there was no quality of life.

So, she started to taper herself, because there were no doctors that would support her. So, she did the work. I think she got in touch with Will Hall and his project. So, very, very slowly she did this and she weighed and measured, and she finally managed to taper, and she was helping other people to make that choice if they wanted to.

Just seeing her in her role and all of her humanness made me just think that this was possible, and then I met more and more ex-psychiatric survivors and was introduced to the Hearing Voices Network and Open Dialogue, and ways for Zach to connect with peers rather than have to take authority from doctors or people that he was by that point quite suspicious of and quite afraid of.

I think that gave me a whole new body of knowledge and just another viewpoint through which to see Zach’s experience.

Moore: The medical model is only one way of seeing these experiences, isn’t it, and as you say, once you discovered there are other ways of seeing it, for some people it becomes a bit less terrifying and a bit less scientific and confusing.

Also, you quite rightly say in the book and again, not for everyone and not wanting to romanticize it, because hearing voices or having visions is terrifying for some people, but some other people develop a relationship with their voices and don’t see them as threatening. So, it doesn’t need to always be following the medical model, does it?

Frank: No, absolutely not. I think that we try to have everybody fit into a certain category or we put square pegs into round holes. Not everybody is the same. We are very diverse and we live in this world with such diverse experiences, and I think that it’s really good that there is more attention now to neurodiversity. I do feel like it’s something that I hear and read more about.

I also think there is a little bit more attention on stories like ours, which I feel is hopeful, but I also at times think that it’s a hard battle because the pharmaceutical industry and the psychiatric model definitely have a lot of money and a lot of power.

So, I think you need your kin to actually walk through this choice. If you are going to take away some of these layers and look a little bit deeper about what might have happened to someone, rather than what is wrong with them. I think having a tribe to do that with is important and I have that, I am really lucky that I do have that.

I have a group of other parents that I can reach out to and talk to, and they are also incredibly smart and well-resourced. One of them used to work as a social worker, one used to work as a psychiatric nurse, and one is an academic. I think it’s almost like a hive mind, where it’s not just about being sad or being worried or trying to get through a tribunal, but about really looking at some of the laws and the things that are very hard to understand in a system that is quite bureaucratic and still quite archaic. So, to have a team to help you through that, I think, is beneficial.

Moore: I couldn’t agree more. Thank you, Tanya. I’d like to go on in a minute, if it’s okay, to talk about reaction to the book, but before you get there, if it’s okay, I just wanted to know how is Zach doing now and how are you doing now.

Frank: There was a lot of anticipation for this book because it took me a long time to write and I felt extremely vulnerable when the book came out. It felt really like being quite naked out there, suddenly. It was not just any memoir but it was a very sensitive memoir, and I also worried a little bit about Zach as well, both of us being quite exposed, but it was also a very exciting time and I felt like it was empowering us to be able to have a voice that went a little bit further, and a voice that was heard because I often feel that my voice isn’t really heard and Zach’s voice has been so silenced that quite often, he doesn’t even talk.

He actually has stopped talking at all, because I think he feels that if he talks about his voices or if he talks about feeling hopeless or wanting to die, I think the response is one that disempowers him further.

So, I think one learns very quickly in that situation to just be silent. So yes, it was very exciting and it had taken a long time. I had a launch party and I had so much support. Also, it has led to discussion. I had a lot of articles come out on both sides of the pond and the book was reviewed in the New York Times, which felt very prestigious to be able to have that attention.

I am kind of thinking that this book might be one that touches some people’s hearts, rather than a book that becomes a bestseller, and I am learning to accept that and have some gratitude around that. I’ve had a lot of emails and messages about how the book has touched people and how their experience is similar, and I’ve been able to also support them, and guide them towards some of the groups that I belong to so that they too can have a voice and benefit from some of those campaigns and some of that advocacy.

Moore: I hope it does become a bestseller. If I were a parent with a child or had a partner who was struggling with some of these experiences, this is exactly the kind of book that I would like to read. You don’t pull any punches, you describe the severe difficulties that Zach has and you have as a family, but also you describe how haphazard the treatment is and how sometimes the treatment lacked compassion and didn’t see Zach as a person. But also there is so much hope in the book in terms of different routes for help.

So, I read it once to do the podcast and now I’m reading it again but from a parent’s perspective, more slowly, and taking time. It’s powerful and it’s beautiful.

Frank: Thank you. Thank you so much. I appreciate that.

Moore: I’m sure so many people will get a huge amount from reading the book, and I certainly did, but you wrote a piece for The Guardian newspaper and a UK psychiatrist on Twitter made quite a telling comment. He referred to it as “anti-psychiatry spin.” When reading the honest, heartfelt reflections of a mother on her son’s treatment by mental health services, people like that can’t even look to improving what they provide rather than giving a diminishing response. I felt really sad seeing that.

Frank: Yes. Me too, actually. Part of me maybe even expected that, as cruel and cutting as it was, just because I think there is such a defensiveness on the part of many psychiatrists. I think that my narrative was perhaps just something that was too challenging and would’ve caused a lot of reflection on their part, and that reflection could probably be painful, I’m sure.

So, I think it’s very easy to just dismiss somebody and to say that they are anti-psychiatry, rather than looking at the fact that, I am not anti-psychiatry, I am anti the very difficult iatrogenic effects of these drugs and some of the ways in which psychiatry can work to take away somebody’s autonomy. That is my personal story.

I think that to use that label as well harps on this idea of the 1960s and psychedelics and R. D. Laing and this whole idea of rebellion. That’s not who I am, and that’s not who I can be even at this time, but yes, I think that to withstand those kinds of comments again, if you are in the field and you are practicing, or you are preaching some way that’s deemed as alternative, I think to be in your camp with others that can make you feel safe is important.

Moore: Tanya, it’s been such a pleasure to talk about your book. It’s thought-provoking, it’s heartfelt, and it’s powerful. It’s beautiful in parts, it’s savage in other parts. The parallels between your experiences and marine life are quite stunning. I think it’s so important that we share personal experience in this way, because otherwise, we do only apply a medical lens, and for people out there struggling with these experiences, we do need to make people aware that there are alternatives and different ways of looking at this. We don’t necessarily have to collude with the medical model as it’s presented to us.

I think you do a fantastic job of talking openly about all that. So, thank you.

Frank: Thank you so much, James. I appreciate it. It’s been wonderful to just be able to have this conversation with you.