Mental distress is a portal to self-actualisation, providing a gateway into inner-consciousness…[it] is only labelled as an ‘illness’ because of how we have been conditioned to understand it within western culture

The above words flowed through me from a liminal space beyond my logical mind during a meditation. Now, twelve years later, the same words were being spoken back to me by my research participants. They had all experienced something similar, but were diagnosed as ‘psychotic’.

Disillusioned after working in the mental health field for many years, I’d found allies within the Critical Psychiatry Network (CPN), focused on promoting the human rights of those diagnosed.

Compelled by my own experience of an altered state of consciousness, and knowing that I narrowly avoided a diagnosis of psychosis due to knowing ‘what not to say’, I wanted to explore further. I began a master’s degree in consciousness, spirituality and transpersonal Psychology in 2021, in the hope that it would shed more light on such experiences.

Artwork by J

Transpersonal psychology examines experiences which include a sense of connection with an expansive, more meaningful reality. A key concept in transpersonal theory is ‘spiritual emergency’, defined as challenging spiritual experiences that can lead to personal growth. However, Transpersonal Psychology still differentiates between ‘progressive’ and ‘regressive’ psychoses, a concept called ‘differential diagnosis’.

I became frustrated with this concept, considering the growing evidence in psychiatry to normalise extreme state experiences that get pathologised as ‘psychosis’ as natural reactions to trauma. I wondered if psychiatry might benefit more from transpersonal theory if the concept of differential diagnosis was abandoned, as Paris Williams suggested.

I therefore decided to explore the gap in research between the fields of psychiatry and transpersonal psychology. As my starting point, I chose to focus on a differential diagnosis criterion which claimed that spiritual experiences promote personal growth over time, whereas ‘psychosis’ lacks the developmental potential for growth. This criterion was opposed by Brian Spittles, who proposed that ‘psychotic’ and spiritual experiences are indiscernible. My research question was:

How do some people find and harness transformative meaning in their experiences conceptualised as psychosis by clinical psychiatry?

Heuristic inquiry felt like the perfect method to use for my study as it has the potential to advance social justice and empower research participants, considered to be ‘co-researchers’ due to the collaborative process and collective wisdom generated.

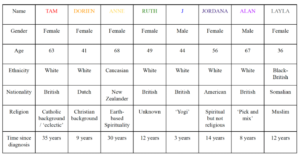

Eight co-researchers (see Table 1 below) were selected via the Emerging Proud blog and social media. Participants were people who had been labelled with psychosis, but found alternative ways to understand their experiences.

Table 1

Co-researcher demographics

During an online interview, co-researchers were asked questions about their experience, specifically factors which catalysed their extreme state, a description of their experience, what support they ideally needed at the time, any specific symbolism or meaning they had gleaned from the experience, and whether they felt their experience was purposeful/meaningful.

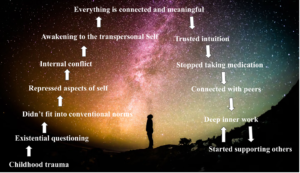

My co-researchers and I shared a similar experiential arc in our life journeys, depicted in figure 1, and through a passage of interwoven direct quotes here. The colours of quotes correspond to co-researchers, as named in Table 1.

Figure 1

Experiential trajectory of co-researcher journeys

Eight main themes were derived from analysing the data into categories of sub-themes, as highlighted in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

Eight main themes and sub-themes

Overall, co-researchers found their experiences meaningful as they offered: “more of an understanding of what it is to be human

All co-researchers reported personal growth as a result of their experience. Factors which led to this included: (1) awakening to the fact that humans are more than physical beings and are deeply interconnected with each other and the world via what are known as exceptional human experiences, (2) the acknowledgement and integration of sub-personalities, and becoming self-led, (3) healing inter-relational attachments through peer support, and (4) connecting with a meaningful life purpose by offering support to others going through similar experiences. Subsequent meaning-making through embracing a positive interpretation of their experiences, consequently supported their transformation.

If, as Spittles proposed and my results indicate, experiences labelled as ‘psychosis’ and those deemed to be spiritual emergency are indiscernible, then it follows that factors impacting how an altered state of consciousnss is framed and supported, rather than the altered state itself, influence the outcome.

I urge that it is now an ethical imperative for transpersonal psychology to abandon differential diagnosis.

Transpersonal psychology could hold the key for ushering in a new paradigm for psychiatry based on its more expansive worldview. However, upholding differential diagnosis as valid is counterproductive to such a paradigm shift. If transpersonal psychology does not acknowledge the need to be trauma-informed and decolonised, it perpetuates the existing stigma and creates further marginalisation.

Māori psychiatrist, Diana Kopua asked how we indigenise our spaces to ensure that transcultural knowledge systems are valued and utilised: this is perhaps the most pertinent question of our time.

Could the wisdom harnessed from extreme state experiences support a positive transformation for psychiatry? My co-researchers thought so. Tam said:

“There are so many of us that are bridges between these worlds and there’s so much that you could learn and you’re just turning your back on this incredible treasure trove of meaning and awareness”

Footnote:

This research was completed with the Alef Trust in 2024.

The ‘Emerging Proud’ campaign promotes crisis as a potential catalyst for transformation if correctly supported. Our ethos is based on the transpersonal and transcultural perspective of extreme states being part of a natural healing process rather than a pathology.

Emerging Proud is having a revival—we have formed a CIC: The ELEPHANT collective.

We call ourselves The ELEPHANT Collective because we draw inspiration from the Indian parable of the blind men and the elephant. Each person, touching a different part of the elephant, describes only what they perceive—a trunk, a tusk, a tail—each believing they understand the whole. Only through sharing perspectives and collaborating do they begin to grasp the full picture. Today, with the richness of diverse cultures, ideas, and beliefs available to us, we believe we can finally start to see beyond our limited perspectives and understand more about the Universe in which we exist.

We are in the process of creating a community platform: Our ELEPHANT, for people to gather, discuss these issues and to galvanise and ground ideas into action. We aim to extend the Overton Window in terms of acceptable public discourse around ‘non-ordinary’ states of consciousness through a new documentary.

A free online discovery call for this is happening on 14th Dec at 7pm UK time. Reserve your place here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/the-elephant-collective-discovery-call-tickets-1083122050209?

****

Mad in the UK hosts blogs by a diverse group of writers. The opinions expressed are the writers’ own.