Using the mental health system in England as a case study, a recently published book chapter argues that social workers have both remained complicit in psychiatric oppression and actively resisted by forming alliances to support radical, service-user-led social movements.

Although social work is not typically thought of as a critical profession in the management of the mental healthcare system, a historical overview sheds light on how the government uses social workers to regulate social welfare services and control the people who use them.

Rich Moth, Lecturer at the Royal Holloway University of London, uses Gramscian theory and a close look at the history of England’s mental health system to argue that changes in social welfare policy are not a coincidence or in response to social need. Instead, the shaping of social welfare systems is deeply dependent on other historical and political moments. This has broader implications for how professionals, including social workers, are trained to interact with people who are direct recipients of state policies that determine mental healthcare and treatment practices.

He argues that “…social work’s development (like that of psychiatry and other health and welfare occupations) should not be understood in terms of an autonomous ‘professional project’ or a spontaneous response to self-evident human need. Rather, state social work is better understood as a highly context-dependent form of institutional activity, conditioned by the nature of the welfare regime from which it emerges and within which it is situated.”

The post-World War II (WWII) period and process of deinstitutionalization illustrate how current social and political contexts prompted a change in social welfare services. At the time, there was rising knowledge and resistance towards the horrendous harms done to people receiving inhumane asylum ‘treatments’ such as insulin coma therapy, electric shock treatment (ECT), and psychosurgeries.

Veterans at the time also pled for psychological and social support from the trauma they experienced at war. This prompted a general policy consensus that led to community mental healthcare and efforts to redistribute social goods for people most harmed by psychiatry, such as people experiencing poverty, women, racialized communities, and LGBTQ+ folks.

However, over time, capitalist governments have continuously adopted neoliberal approaches to mental healthcare. Such approaches (1) fail to recognize and address structural problems, such as poverty, which directly contribute to mental distress, (2) very poorly invest in social services, even when community-wide support is promised; and (3) instead place responsibility on people to take care of themselves through medication compliance and other individualized solutions.

According to Gramsci, this process is deeply entwined with the goals of the “integral” or capitalist state, which uses both consent and force to control people, maintain social order, and support capitalism.

In this context, consent occurred after the asylum and post-war period when the state responded to a call for change and developed community-based approaches to mental healthcare. Although promising, in contention with this were social workers who were trained to surveil or monitor these systems and identify people who deviated from owning individual responsibility for their mental distress (e.g., rejecting the use of psychotropic medications).

This led to punitive consequences that can be seen in “the controversial Mental Health Act reforms [which] introduced pre-emptive detention, increased spending on secure institutions and restrictive community treatment orders, and [led to] a rise in the number of people with mental distress [who are] incarcerated.”

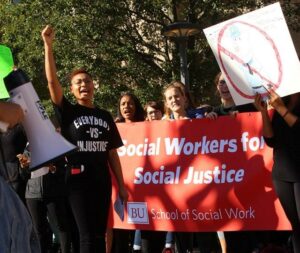

Despite the social work profession’s complicit role in perpetuating oppressive practices in psychiatric care, radical social workers have also served as activists who have formed strong alliances to support anti-psychiatry movements and fight for social justice. Such approaches have rejected the neoliberal approach to blaming individuals for mental illness and have fought for the state to pay more adequate attention to how social inequality causes individual and intergenerational mental health problems.

Although this argument is based on an overview of institutionalization and oppression within the mental health system in England, similar government practices occur internationally, and social workers will continue to occupy critical roles where they assist in enacting and regulating state policies.

Therefore, understanding how professions (such as psychiatry and social work) have perpetuated harm in mental health service contexts is an essential first step in disrupting the underlying capitalistic system that fuels such practices through institutional harm.

Some social workers already advocate for how their profession should encourage and respond to a “post-psychiatry” world, especially as neoliberal culture worsens mental health by promoting individual isolation and community disruption. However, controversy about the social work profession persists, especially in light of social work being proposed as the ultimate solution to eradicating violence in the criminal legal system through defunding the police.

However, in line with this current argument, some wonder whether social workers are really a less harmful solution since they still abide by a system designed to control marginalized people who are most vulnerable to the oppressive practices enforced by the state.

****

Moth, R. (2023) Institutionalisation and oppression within the mental health system in England: social work complicity and resistance. In V. Ioakimidis & A. Wyllie (Eds.), Social Work’s Histories of Complicity and Resistance: a Tale of Two Professions (pp. 165-182). Policy Press. (Link)

Editor’s Note: Part of MITUK’s core mission is to present a scientific critique of the existing paradigm of care. Each week we will be republishing Mad in America’s latest blog on the evidence supporting the need for radical change.