Image provided by Jessica Fairfax Hirst

Editor’s Note: This interview by Laura López-Aybar originally appeared on our affiliate site, Mad in Puerto Rico.

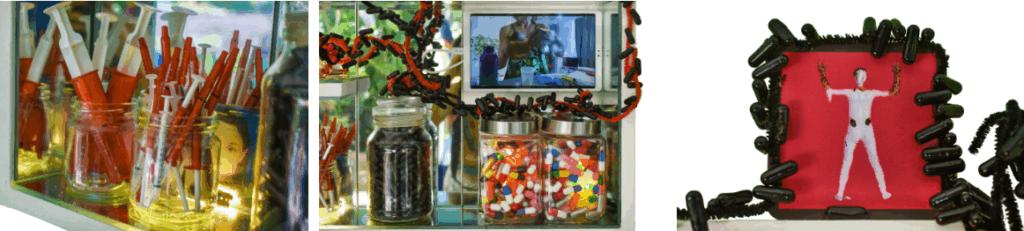

In this conversation with artist Jessica Fairfax Hirst, we explore the process behind her “Withdrawal First Aid Kit” art installation, recently awarded at the National Biennial of Visual Arts in the Dominican Republic. Hirst shares how her personal experience of withdrawal from psychotropic drugs evolved into a multidisciplinary work that combines objects, video, and performance, questioning biomedical discourses on mental health. From a critical and human perspective, the artist reflects on the power of art to make visible the effects of medicalization, the lack of information about withdrawal, and the parallels between the pharmaceutical industry, the climate crisis, and the colonial structures that sustain them.

Laura: Thank you for sending us your work. I’m so happy that we connected and have this space, because I think it’s very necessary. Not long ago I saw a piece about the troubled teen industry—those programs where they lock up adolescents. They showed all the personal belongings hanging from the ceiling in bags, just like they’re returned to you at the end of the program. I think it’s important to talk about this because the art world often adopts the biomedical discourse instead of a more critical line.

Jessica Hirst: I started out making art within that biomedical discourse because I didn’t know any different. I had my first experience with withdrawal in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but I didn’t know it was withdrawal. Every doctor I had in the US diagnosed me with a “relapse” or a worsening of my “illness.” I basically understood that I was always going to be a “severely mentally ill” person as my destiny.

I stayed like that for more than ten years—very unstable, with such deep anguish that I wanted to be dead. When I began making art, I thought the mistake was mine, for trying to stop the antidepressant.

That’s why I entered the art world following the biomedical line—out of ignorance. Even here in the Dominican Republic, in 2013–2014, I did an exhibition called “Medication.” Now, years later, I can see my confusion, because in the catalog I repeated the biomedical discourse—that certain people have to take medication for life—but at the same time I was painting large abstract canvases based on the chemical formulas of my medications. It was an aesthetic exploration of neurochemistry, an attempt to understand what was happening to my brain and body.

It took me a long time to reach a more critical position because I had so much trauma and believed doctors must have the answers. That changed in 2021, when I saw the documentary Medicating Normal. My husband saw it online dubbed in Spanish and said, “Jessica, come here, I think this is your story.” And he was right.

Laura: If you want, tell me a little about how you came to this piece, the “Withdrawal First Aid Kit.” How did you conceive it? How did you turn your experience with withdrawal and tapering into this artwork?

Jessica: In my bathroom I have a small medicine cabinet made of MDF wood that I designed and had built by a craftsman. I was taking lithium in liquid suspension; the pharmacy would send me more than I needed, and it would expire after 90 days. So I had old bottles with that liquid that separates—the denser white substance of the medication on the bottom, and the clear suspension liquid on top. I watched it for months. One day I thought: what if I put my photo where the medication label is? That’s how I began to shape the idea in my mind.

The Dominican National Biennial of Visual Arts is the oldest Biennial in the Americas—it’s now in its 31st edition. To participate as a foreigner you need five years of legal residence. Every time I renew my residency it takes a really long time to process, so this was the first time I could participate, even though I’ve lived here for eight years. I was super excited and wanted to do something at the level of what they might accept.

Before that I had done another exhibition based on large wooden boxes—three-dimensional collages with objects. It wasn’t about medication, but I like to work with compositions of everyday objects out of their original context. I also trust in “happy accidents” and experimentation: I don’t have an exact plan; I just try things and see what happens.

The sensation of withdrawal the year before I made this piece was like drowning—my senses hypersensitive to noise, to visuals, to people’s energy, to heat; also, a very intense physical anxiety, difficulty concentrating on my work, a reaction to an antibiotic that put me in a state of extreme agitation for several days, etc. All of that experience became input for this piece, with my ID photos sinking into that denser white part of the liquid lithium, like quicksand.

Laura: Like quicksand…

Jessica: Exactly. Through experimentation, the video came next. I’ve worked mainly in performance for many years, with the idea of using the body, space, and time as art materials, just like wood or stone or paint. I wanted that long-term feeling of tapering, which takes years.

I started filming myself three years ago doing this daily process: dissolving the bupropion pill in water, measuring it with syringes, taking notes. The withdrawal symptoms caused so much confusion that it was sometimes hard to do the most basic math to reduce just a little bit each day or week and record it. I was filming that for several years, and when I traveled, I filmed the process in other places so that when you watch it, you get a visual sense of how long it takes. There was also a period of several months where my withdrawal symptoms were so bad that I had to move out of my house, because I couldn’t tolerate all of the bright colors and art that I myself had created. I also couldn’t handle being around other human beings. I stayed in three different little apartments where the walls were white and I didn’t have to see anyone all day, basically making my own personal withdrawal clinic. I filmed the tapering process in each of those places, and I also did more performative actions related to how the tapering felt to my system. I don’t know if I sent you the video—I can send it to you.

Laura: I think I saw a clip of you showing the notebook, filling it out, but I didn’t hear it as long as you’re describing now.

Jessica: Yes, I took all that video material and sped it up super fast, so the process of several years could be seen in a few minutes. I can send you the full video link—it’s about three minutes. People don’t have much patience in an exhibition for long videos.

Laura: And what have the reactions been to these pieces about your withdrawal and medication tapering process?

Jessica: Well, I’m still seeing that. Last weekend I was in Santo Domingo—I live five hours away—and I talked to many people who came to the museum about my piece. Here there isn’t much awareness about psychiatric drug withdrawal; I didn’t talk to anyone who had direct experience. But I did find many people who are critical of the healthcare system in general. They shared experiences with medications for asthma or other conditions, and that feeling of being trapped.

Several people told me “the healthcare system makes more money from us when we’re sick than when we’re healthy—they don’t want us to heal.” That level of critical awareness surprised me a bit, but I think it’s related to the fact that Dominicans have extensive experience with corruption, so they don’t trust institutions in general as much as people in the United States usually do. And that extends to doctors. Also medicines are expensive; insurance doesn’t cover everything. So Dominicans may be more likely than people in the United States to ask, “Why do I have to take a pill every day for the rest of my life?”

Laura: Right, questioning what the intentions behind all this are.

Jessica: Exactly. We’re trying to organize an event at the museum in two weeks with other artists to talk about our artworks [update: we weren’t able to hold the event at the museum because of bureaucratic incompetence and political infighting. We are trying to find a different venue for the conversation]. My “withdrawal first aid kit” won an award from the Biennial, and it’s been in the press several times. Even though I put a very didactic text on the wall next to the piece explaining the topic of psychiatric drug withdrawal in the Dominican context, the articles only describe the work in very general terms. That’s fine, but they don’t mention what’s behind it. The impact of the piece here remains in questioning that sense of dependency on medication for any condition, not just mental health.

Laura: It’s interesting because now I’m seeing more newspaper articles about the side effects of medications and withdrawal symptoms. It’s becoming more common. At the same time, what you’re saying reminds me of the trend to generalize psychology—to treat it as a physical condition rather than as part of the human experience within the political and structural systems we live in. That’s interesting too, because it keeps taking things out of context.

Jessica: Yes.

Laura: And I wanted to ask—you have photos, you have the video—have you done any live performances with your body in space? I know you’re not there now, but I don’t know if you plan to do any kind of intervention or if you’ve done that before. Why is it important for you to make this a multidisciplinary work?

Jessica: Well, I didn’t propose a live performance because the biennial committee introduced a new requirement for performance art. Performance artists here felt those rules were inconsistent with the practice of performance art —they were more for theater. They wanted us to do the performance three times: once for the selection jury, once for the awards jury, and once at the opening. They had other requirements that made us think, “This isn’t performance; this is theater.” So I decided not to propose anything live.

I have made several performances about this topic. I’ve done them in Madrid, New York, and one at the Centro Cultural de España in Santo Domingo in April called Psicofarm/Atmosférica, which explored the connections between psychiatric drugs and the climate crisis. But at the biennial, I couldn’t propose that kind of intervention. Through the Dominican Performance Platform we sent an open letter to the Biennial Commission with our critiques of the rules. They told us they’ll take our feedback into account for the next biennial. We’ll see what happens.

Laura: For me, the multidisciplinary aspect also makes sense as an analogy to withdrawal—it consumes you completely, touches all the senses, all the foundations, and requires a multifaceted, multisensory approach. That’s why I see your work using photography, video, audio, body, paint, blood, colors…

Jessica: Very good point. In the future, I’d like to return to more immersive performances. For example, years ago I did one where I estimated how many pills I had taken over the years, filled a bucket, and invited the audience to put their hands in to feel the texture of thousands of capsules. I also began covering my body with pills for the multisensory aspect.

In one performance two men represented psychiatrists and covered me with colored empty capsules glued on with honey. Then they called out to the audience: “Come take your medicine,” just like they do with patients in psychiatric hospitals. They lined people up, and participants took an empty capsule from my body and had to swallow it. In this Withdrawal First Aid Kit piece, there’s photo, object, and video-performance, but it’s not as immersive as other things I’ve done or want to do.

Laura: I really liked the video. When I saw your notebook with the list I thought, “Wow, what a responsible person!”

Jessica: It’s not that I’m responsible; it’s that my mind in withdrawal had all the symptoms of attention deficit and memory loss. I couldn’t even see clearly to measure with the syringe. I tried not to make mistakes, but it was a mess. I’d always been good at math, and now…

Laura: You can visualize the time period, how systematic this process is. People think they know—and I don’t know if it happened to you—but I’m almost sure they didn’t tell you, “If you try to stop the meds, this is what will happen; there’s a high chance you’ll experience all these symptoms.” They don’t tell people that.

Jessica: Exactly. When I think about my piece, I know there are people in that situation. I supposedly went to the best psychiatrist in Santo Domingo, and he told me, “No, this medication doesn’t cause withdrawal.” And I said, “Yes, I’m experiencing it.” He insisted it didn’t. I know there are patients of those doctors who are in withdrawal and don’t know it. If one or two people can see my piece and at least realize it, it’s worth it.

Laura: And they prescribed you more medication, right?

Jessica: That’s what happened to me—and to many others.

Laura: Right, they give you another medication to treat a side effect, and you end up with more side effects.

Jessica: Exactly. I haven’t found clear statistics on what percentage of the Dominican population is medicated with psychiatric drugs. I think it’s much less than in the United States or Europe, and that may mean fewer people go through withdrawal, but it’s true there’s a lack of information and resources.

Laura: There’s also probably a stigma around seeking psychological support for emotional well-being.

Jessica: Yes, it’s a problem. I see anti-stigma campaigns, and they’re often literally funded by pharmaceutical companies so you won’t feel ashamed to get medicated. But that’s not seeking therapeutic help, to talk to someone and process—it’s seeking medication. I even spoke at the museum with someone doing her internship to become a psychologist at the psychiatric hospital, and she told me she doesn’t like seeing the effects of medication on her patients. I thought: that’s good—that experience might help her later in her career to support people differently.

Laura: My next question is: you’re a specialist in public policy on environmental change. How do you see the relationship between these policies, climate change, mental health, and the pharmaceutical industry?

Jessica: I see many parallels. It sounds cliché, but it’s neoliberal capitalism—greed. I started my career working in climate policy, seeing so many years of work, commitments, and then countries failing to meet their promises to the UN. Why? Because a small group makes too much money from unsustainable systems, even when they harm humanity.

It’s the same with psychiatric drugs—there’s greed for money and power. The whole system is built on the diagnostic manual, which is absurd when you look at it. I even did a performance years ago called Diagnosis: I was in an office, the audience came in one by one, I opened the DSM at random, chose a diagnosis, and read it aloud to the person. That became their “diagnosis.” And most people told me they could convince themselves that they had several of those symptoms on the diagnostic checklist.

It’s not just the pharmaceutical industry—it’s also the stock market, the investors. The whole system is designed to keep numbers high, no matter the real-world impacts of their products. ExxonMobil, the oil companies, the pharmaceutical companies—it’s always the same.

Laura: An article just came out saying withdrawal doesn’t exist, and when they investigated, the psychiatrists who wrote it had received thousands of dollars from pharmaceutical companies.

Jessica: Exactly, I saw that. I also have a book I love—Crazy Like Us.

Laura: I have it too!

Jessica: I’m not surprised. The book shows how pharmaceutical companies paid anthropologists in Japan to create the idea of Western-style depression, which didn’t exist in their culture. They made people put their emotions into the same boxes as the West. It’s colonialism.

I describe the climate crisis as “atmospheric colonialism”: certain countries fill the atmosphere with gases that affect everyone else. It comes from the consumption patterns of Europe, the U.S., and now also China. There are many parallels.

Laura: It’s also been exposed that they pay influencers on social media to normalize diagnoses and medications.

Jessica: Yes, and it’s very sad. Many young people, with real anguish, end up building their entire identity around a diagnosis.

Laura: It’s very concerning what’s happening. I’m curious about how you ended up living in the Dominican Republic?

Jessica: I could not get better in the United States. I was very ashamed for years that I was disabled and could no longer work on climate change policy. Whenever I would meet new people in the DC area, their first question to me would be “So what do you do for a living?” And because I did not have an impressive answer, I felt devastated and inferior.

It wasn’t until I went moved to Nicaragua in 2006 that I began to realize the role of my cultural context in dealing with the devastation that withdrawal had made of my previous life. Being there, nobody asked me what I did for a living. I finally had the mental space to explore who I might be if I wasn’t going to be a high-powered climate change policy person.

I use a metaphor based on my studies of ecology, that each of us could be compared to an animal that has a different range of conditions under which we can survive, or thrive. I feel as though I have a very permeable skin, kind of like a frog or another amphibian. These animals were some of the first to exhibit big impacts from endrocrinergic chemicals in the water that disrupt reproduction, leading to significant bodily deformations. I feel that I am super sensitive to some of what’s “in the water,” or perhaps better to say in the air, in the United States: the competition, the emphasis on achievements, and the pressure to “be productive.” That sensitivity is less triggered in the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua.

I definitely do not view the Dominican Republic as the vacation paradise that many people in the US see it as. Every year that I am here, I experience and learn more of the serious structural problems, injustices and difficult political culture. But I also have found here a habitat in which I can survive, and sometimes thrive.

Laura: How do you contextualize your lived experience of migration and psychiatric violence to the sociopolitical climate?

Jessica: I have quite a number of disabilities that make it very hard for me to function in the United States, or even Spain. Due to the variations in intensity, timing, and type of symptoms I face either from the long-term adverse effects of psychiatric medication, or from withdrawal, it can be very difficult for me to keep the kind of schedule or commitments that are considered normal in the United States or Spain or Germany. Depending on how I’m doing, it can be very hard for me to keep commitments to be at specific places at specific times, and in general, the culture in the US or western Europe is not very accepting of people who can’t show up when they’re supposed to.

Calling attention to the Western preoccupation with productivity is part of a disability arts lens—or as Thich Nhat Hanh said, “We are not human doings, we are human beings.”

This is something that is much more normalized with crip culture. I had to withdraw from my MFA program in Los Angeles in large part because their understanding of “reasonable accommodations,” as stipulated in the Americans with Disability Act, did not match what I needed. They told me that I would fail a course if I missed more than two sessions. I became so depressed and dysfunctional in Los Angeles that I couldn’t even answer the phone, and some days I couldn’t leave the house.

Dominican culture is much more accommodating, although it’s not based on Disability justice or crip-ness per se. The frequency with which people cannot show up, or have to postpone, or are late, or can’t meet their commitments, can be frustrating for me and for others, and can be a point of contention for both Dominicans and outsiders. At the same time, it is this very characteristic, that people here are just more accustomed to uncertainty, by necessity, that makes it a much more accepting habitat for me and my disabilities. Dominicans and Haitians are in general much more understanding if I have to cancel, or if something has to change.

In fact, it is so normal to not be able to keep a commitment, that Dominicans reflexively say “I’ll see you tomorrow/I’ll see you at the meeting/si Dios quiere—if God wills it.” When I first arrived, I thought it was a sign of a very religious culture, but now I understand it quite differently: there are so many aspects of life here that are out of someone’s control that they can’t be even 80% sure that they will be able to keep any particular commitment. It could be seen as putting it in God’s hands, and it could also be seen as just a short-hand for acknowledging the level of uncertainty that pervades everyday life.

Jessica Hirst: I am a multidisciplinary, disabled, and neurodivergent artist. I work primarily in performance, video, installation, 3D collage, and social practice. I grew up outside the U.S. capital Washington DC and studied at Stanford University in “Earth Systems,” later working under President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore in climate change policy. I went through traumatic antidepressant withdrawal at the end of the century, which forced me to leave my environmental policy career, become a dance teacher and choreographer, and over the years, transform into a performance and visual artist. I have been a refugee since 2006 from the toxic habitat of the United States, having lived in Nicaragua (2006–2009), Spain (2009–2012 and 2018–2020), and the Dominican Republic (2012–2016 and 2020–present).

I work through an expanded process of site-specific creation, on topics such as neurodiversity and other forms of difference, psychiatric drugs, sociopolitical issues like the ongoing impacts of U.S. interventions in Latin America, and various aspects of the climate crisis and our place in the ecosystems we inhabit. I argue that the climate crisis and the problems surrounding psychiatric drugs share the same root—neoliberal, corporate, corrupt capitalism, lacking control and ethical conscience. In my art and my life, I try to become aware of my privileges and cultural conditioning, and I seek collaboration with people in my community in Puerto Plata province. I feel that this community has allowed me to participate and belong, with all the challenges and difficulties, in a way very different from my experiences in the United States.

I’ve presented performances, exhibitions, and residencies in countries such as India, Thailand, Germany, the United Kingdom, Spain, Austria, Zimbabwe, Senegal, Chile, Brazil, Finland, Serbia, Latvia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Italy, Nicaragua, the United States, and Japan, among others.

In addition to my Stanford degree, I have studied at UC Berkeley’s Energy and Resources Group, Psychology at Johns Hopkins University, Contemporary Art at Metáfora Barcelona, and Public Practice Art at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles.

WITHDRAWAL KIT