In a new study, researchers Jim van Os and Peter Groot found that when trying to discontinue antidepressant use, a process of hyperbolic tapering reduced the likelihood of withdrawal. Withdrawal symptoms were further reduced by slowing down the process and tapering in small daily steps rather than in large decreases every week.

Reached for comment via email, Groot wrote:

“Our research confirms what patients have known and been trying to achieve for decades. That reducing the dose gradually enough and in small steps gives the body enough time to get used to the slowly decreasing dose and prevents complaints due to withdrawal.”

Since a variety of factors can influence antidepressant withdrawal in complex ways, they suggest that the specific, individual process of tapering should be monitored and adjusted in a personalized manner. The authors write:

“The demonstration of multiple demographic, risk, and complex temporal moderators in time series of withdrawal data indicates that antidepressant tapering in clinical practice requires a personalized process of shared decision making over the entire course of the tapering period.”

Antidepressant withdrawal is common in those trying to get off the drugs and can be severe in up to half of those who experience it. The UK NICE guidelines now acknowledge the potential for severe and long-lasting antidepressant withdrawal. Researchers have proposed that a hyperbolic tapering schedule may help prevent withdrawal or at least reduce the severity of symptoms.

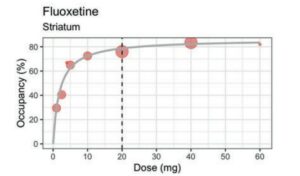

A hyperbolic taper means that the dose has to become smaller and smaller, particularly near the lowest doses. This is because the drug occupies a large proportion of the brain’s serotonin receptors even at a very low dose (see the dose-occupancy graph below for fluoxetine). As the graph shows, dropping from 40 mg to 20 mg will not make much of a difference in terms of the drug’s effect. However, dropping from 5 mg to 2.5 mg means going from around 65% occupancy to 40% occupancy, a significant shift in the brain’s serotonin system. Going from 2.5 mg to a complete stop is an even sharper drop in serotonin occupancy: dropping from 40% to 0. Thus, as the dose approaches zero, smaller and smaller incremental changes may be necessary to give the brain time to adapt.

As van Os and Groot explain, “When a psychiatric drug is administered, physiological adaptations occur, and a new homeostatic set-point is established. Abrupt drug discontinuation leads to withdrawal symptoms, with their duration determined by the time needed for the adaptations to resolve. These symptoms may worsen or peak even after the drug is eliminated. Tapering, or step-wise reduction of the drug, causes withdrawal symptoms at each step, but with lesser intensity than abrupt discontinuation as a new, lower homeostatic set-point is established before further dose reductions. Drugs with longer half-lives may lessen withdrawal symptoms by minimizing the difference between the shifting set-point and plasma levels. Also, according to the model, a more gradual step-wise reduction further lowers the risk of withdrawal symptoms.”

Unfortunately, antidepressant pills don’t come in an easily reduced form, which leads patients to try to cut them and break them into small enough doses—which doesn’t lead to very precise dosing. One solution to this issue is tapering strips, which have been used in the Netherlands recently. A patient can order a set of personalized tapering strips from one particular pharmacy in the Netherlands, which contains antidepressant medication packaged in the doses required for hyperbolic tapering.

In previous studies, van Os and Groot found that tapering strips helped users to successfully stop antidepressants by reducing the likelihood and severity of withdrawal. In one study, for example, tapering strips helped 71% of users to successfully discontinue antidepressants, most of whom had unsuccessfully tried to stop using the drugs before.

The new study by van Os and Groot aims to provide a clearer picture of how tapering and withdrawal are linked and what other factors might be involved. The study included 608 participants in the Netherlands who used tapering strips to try to discontinue their use of antidepressants. Most received tapering strips with small daily dose reductions, but 8.6% received strips with larger, weekly decreases. Participants rated their withdrawal symptoms daily. The minimum time of tapering was 28 days (one set of tapering strips), and the maximum was 140 days.

On average, participants noted withdrawal scores between “very little” and “a little,” meaning that tapering seemed generally successful at reducing withdrawal.

Via email, Groot wrote:

“There were quite a few people in our study who reported no complaints at all during their taper. I was surprised about this because I expected more variation in the numbers patients would fill in on the self-monitoring forms that came with the tapering strips.

Today I am not so surprised anymore. This is because five months ago I decided to taper the venlafaxine I have used since 2004 for the second time. I decided to taper from the 75 mg I was using to 0 mg over a period of 20 weeks with the help of five consecutive tapering strips.

When I started, I intended to carefully fill in my self-monitoring forms every day. But I quickly noticed that I found it hard to do this. Day after day, I took my daily dose without really thinking about this, and time and time again, I forgot to fill in my daily number on the self-monitoring form. Because there was no need for me to do this. Whether I filled it on each separate day at the same time or retrospectively after a week or after two weeks really did not matter. Because the number I needed to fill in was always the same, it was always 1 because I had no complaints, which I could in any way attribute to withdrawal.

This five-month tapering from 75 to 0 mg in daily steps was clearly different from my eight-week taper from 150 mg to 0 mg in weekly steps about 10 years ago.

A week from now, I will be at 0 mg, and then things start getting interesting for me. Will I remain stable or not? If I remain stable, I will conclude that perhaps I have been using venlafaxine for almost 20 years for not very good reasons.”

In their study, van Os and Groot found that, on average, those who tapered faster had worse withdrawal. Therefore, the researchers write that guidelines should allow people to craft personalized tapering schedules that can last much longer than 28 days to reduce withdrawal.

van Os and Groot also note that other risk factors appeared to influence the possibility and severity of withdrawal, including female sex, younger age, previous withdrawal experiences, long-term antidepressant use, and fear of withdrawal. They write that the presence of these risk factors further necessitates a personalized and monitored antidepressant discontinuation process.

They note that the study was observational, so causality cannot be inferred. They add that patients who had already chosen to use tapering strips and who are all in the Netherlands may not be representative of all patients who wish to discontinue using antidepressants.

****

van Os, J., & Groot, P. C. (2023). Outcomes of hyperbolic tapering of antidepressants. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. Published online May 9, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/20451253231171518 (Link)

Editor’s Note: Part of MITUK’s core mission is to present a scientific critique of the existing paradigm of care. Each week we will be republishing Mad in America’s latest blog on the evidence supporting the need for radical change.