I started my antidepressant taper on May 12, 2017. Just over two years later I have managed through grim determination to get down to 25% of my starting dose. The last 755 days represent an almost constant battle with a range of physical and psychological challenges. I wake in the morning feeling utterly exhausted and so fatigued that I can’t think straight, and the day generally goes downhill from that point.

My own mental health challenges were awful for myself and my family. I struggled with anxious thoughts, an intense sense of bleakness and a vomiting phobia and these issues cost me my career, our family home, the loss of friends and colleagues along with my dignity and any self-respect. In retrospect, my withdrawal experience feels far worse than those stark and terror-filled times. My feelings of utter despair or sheer, unreasoning panic were not constant, they abated, at times they were gone completely. Withdrawal does not abate, it is a cloying, near-permanent unwelcome companion that has come to dominate my life and fundamentally affect my family.

While I realise that not everyone experiences such difficulty coming off the drugs, it has been apparent for some time that antidepressant withdrawal needs more attention. A recent systematic review by Professor John Read and Doctor James Davies found that, on average across several studies, 56% of antidepressant users reported withdrawal symptoms. Critics (mainly prominent psychiatric researchers) were quick to point out that self-selected surveys are not necessarily free from bias and that a small sample doesn’t prove that the problem is sizeable. However, here’s the thing, these drugs have been in use for decades, millions of pounds have been spent investigating them to try and understand how they work. So why don’t we know more about long-term effects including withdrawal difficulties and the capacity of these drugs to result in dependence? Withdrawal effects have been witnessed during the placebo washout stage of clinical trials of psychiatric drugs. At the start of the trial, participants are taken off active medications and given a placebo. The intent is to reduce the influence of competitor drugs and to identify placebo responders. What this actually does is pitch the trial participants into withdrawal if they were already using a psychiatric drug. We know that these effects have been seen in clinical trials, yet patient advocates are often met with denial and disingenuous accusations of ‘pill-shaming’ or being anti-science.

Papers discussing withdrawal are almost impossible to find in the big medical journals, often appearing in smaller, independent publications. When a paper does appear, such as the recent study by Doctor Mark Horowitz in the Lancet Psychiatry, it transpires that the only responses allowed are critical ones. I know because I submitted my own response and assisted with the drafting of another on behalf of professional colleagues; both were supportive of the study and both were refused as they only wished to publish critical replies. This in spite of the Lancet Psychiatry wanting to encourage more ‘patient opinion’ with the paper Service User Reviewers: extending peer review in The Lancet Psychiatry from September 2018 asking the question:

‘How can they ensure that those with the biggest stake in decisions made over the future of psychiatry – people with personal experience of mental health problems – are a substantial, indeed a leading, part of the drive towards better care?’

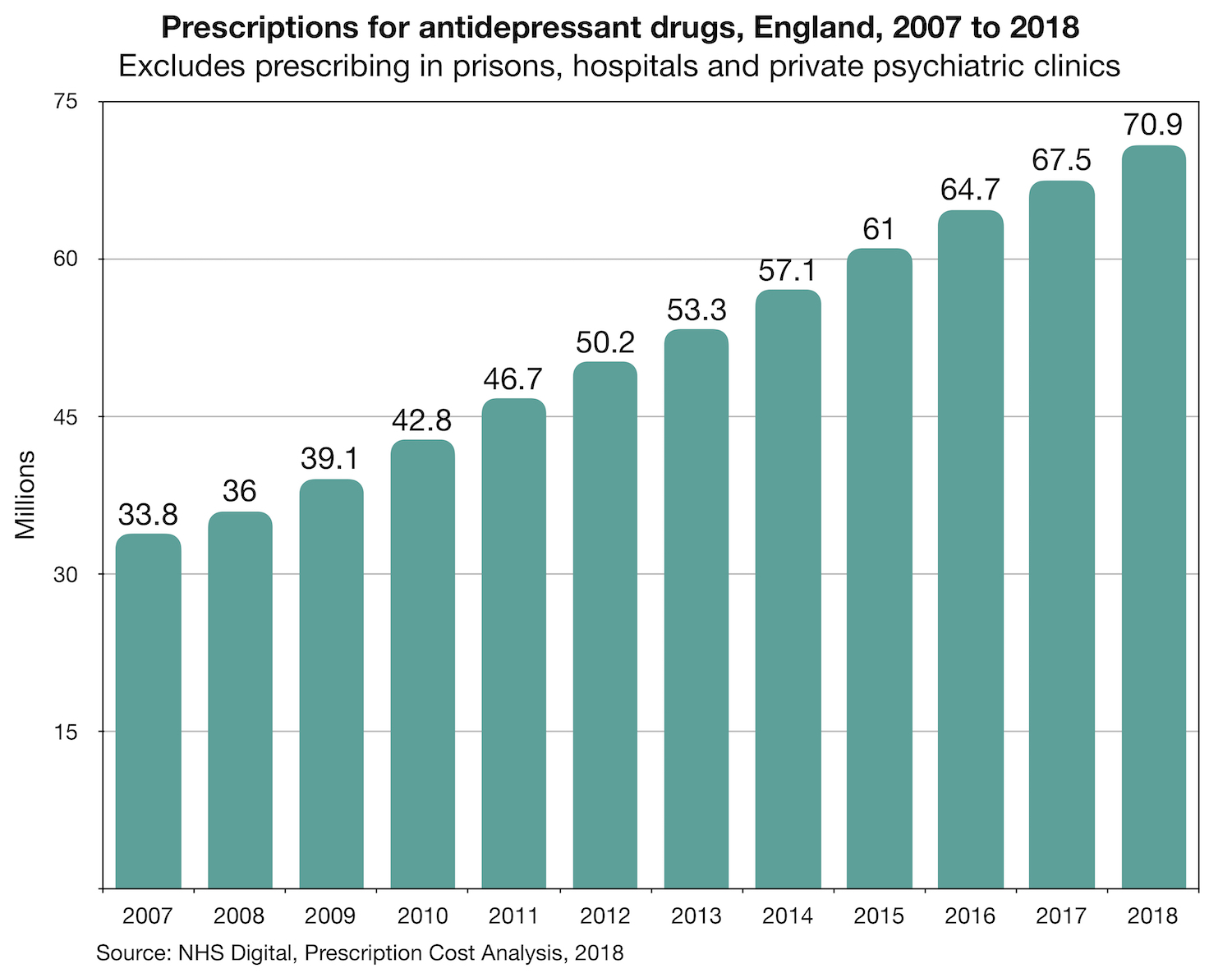

Across England in 2018, we prescribed 71 million antidepressant drugs, a near doubling in a decade. This startling figure is not even the full story as it excludes prescribing in prisons, hospitals and private psychiatric clinics. The Guardian recently reported that there are 4 million long-term antidepressant users in England. Some of those people may well want to rely on the drugs for the rest of their lives, that is their choice and should be respected, but some will have tried and failed to come off. They may well have visited their doctor or psychiatrist complaining of withdrawal symptoms but being told that they had relapsed and their mental health issues had resurfaced. It is a cruel irony that withdrawal symptoms are, at times, very difficult to distinguish from mental health problems as they encompass such a wide range of adverse physical and psychological effects. Many people who have experienced withdrawal, however, will describe tell-tale symptoms that never featured as part of their originally diagnosed condition, but only became apparent once they started to reduce the drugs. For myself, this means crushing headaches and blurred vision, a sure sign that my body is pleading with me to ‘slow down’.

It is now generally accepted by doctors that benzodiazepine drugs such as Valium and Lorazepam can result in dependence quite quickly and care should be exercised when prescribing. Plenty of prominent psychiatrists have spoken out to insist that antidepressants do not result in dependence. Recently circulated by the Royal College of General Practitioners is a guide to the ‘Top Ten Dependence Forming Medications’ from which antidepressant drugs are omitted. To my mind, it has never been proven that antidepressants don’t create dependence when taken for more than a few months. It is therefore incumbent on psychiatry to prove what it says to be evidentially true. In 2014, Professor Peter Gøtzsche at the time a Director of the Cochrane Collaboration, writing in the Lancet Psychiatry, made the following statement:

“We noted that withdrawal symptoms were described in similar terms for benzodiazepines and SSRIs and were very similar for 37 of 42 identified symptoms. However, they were not described as dependence for SSRIs. To define similar problems as “dependence” in the case of benzodiazepines and as “withdrawal reactions” in the case of SSRIs is irrational. For patients, the symptoms are just the same; it can be very hard for them to stop either type of drug.”

On May 29th, the Royal College of Psychiatrists issued a Press Release which signalled a change of position in accepting that some people struggle with difficult withdrawal experiences. It also published a revised policy statement, calling on NICE to update its withdrawal guidelines. This welcome development follows many months of work by the Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry, along with members of the prescribed-harm community. While we should celebrate this significant progress, we do need to be aware of the positioning of formal statements. Towards the end of the ‘Position statement on antidepressants and depression revised policy statement’, there is a section which notes that antidepressant dependence is a matter of ‘public perception’. So while this change of position is welcome, there is still clearly a gulf between the experiential knowledge gained through taking and trying to stop the drugs and those that have gained their knowledge through reading papers and clinical observation. However, bridges are being built and I would like to publicly acknowledge all the efforts that have been made to get us to this point.

“If there is no struggle, there is no progress” – Frederick Douglass

Throughout my own withdrawal, I have been interested in solutions to this problem and have campaigned actively for greater awareness and understanding, launching a podcast and starting a petition which is now well over 10,000 signatures. I loudly applaud the excellent work undertaken by Doctor Peter Groot in the Netherlands to develop tapering strips. An evidence-based solution developed from a lived experience perspective and independent of the drug manufacturers. Let us hope that we can be forward thinking enough to adopt solutions rather than make grand statements while achieving little of practical value for those struggling.

In my campaigning efforts, alongside others, I stand for:

- Support for those affected by antidepressant dependence.

- True informed consent and discussion at the point of prescribing that will help to minimise the chances of someone becoming dependent.

- Fit for purpose, evidence-based guidelines that give the unadulterated facts, not theories.

- Greater expertise amongst doctors and psychiatrists enabling them to recognise and respond to difficult withdrawal.

- Proportionate use of antidepressant drugs with the person being in control of what they take and when they stop.

I believe that such aims are common-sense actions that will minimise harm and lead to better prescribing. Surely a laudable aim for medicine as well as for society.

As for me, I still have the most difficult part of my withdrawal ahead of me, I am fatigued beyond words and dispirited beyond belief. I feel in no way prepared for the challenge ahead. My life has been largely reduced to watching others get on with their lives rather like observing the world from inside a fishbowl. I am very fortunate to be able to work with supportive colleagues who understand that I may be functioning one day and bed-ridden the next. My heart goes out to anyone experiencing withdrawal but especially those surrounded by unsupportive judgemental people, and those who are so ill they can’t work and are struggling to navigate a heartless and cynical ‘benefits’ system. Denial and minimisation of withdrawal make it even more difficult for those suffering to access help, support or seek understanding. Their only crime is to have experienced difficulty from a prescribed treatment, yet they are treated as medical pariahs.

If you do rely on your doctor or psychiatrist for withdrawal or tapering advice, you may experience a very hit and miss approach. Withdrawal from antidepressant drugs can be a significant challenge and needs to be approached carefully, with understanding and a shared decision-making approach. I want to acknowledge the brave general practitioners, psychiatrists, psychologists and researchers who have stepped away from the party line to present the raw, unadulterated truth about psychiatric drugs, including their ability to result in sometimes excruciating withdrawal experiences.

I have no wish to frighten anyone, so it is important to know while reading this that not everyone will experience such difficult withdrawal. This issue does come down to more than a difference of opinion though, we have to carefully judge whether the lack of a full and frank discussion between prescribers and patients is causing societal harm.

To anyone reading this who is concerned or may be unable to find help and support, there are some online resources that can be recommended. Mad in America hold a Provider Directory, listing therapists who are willing to support people who have made a choice to stop. The well-known website Surviving Antidepressants has provided peer tapering support for many years. Another excellent source of information is Laura Delano’s Inner Compass and the Withdrawal Project.

I sincerely hope that I won’t be writing another blog at 1,095 days but I am far from confident.

“Without deviation from the norm, progress is not possible” – Frank Zappa

Thank You James,

I see today:-

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/17692699.psychiatrist-peter-gordon-claims-royal-college-gaslighted-him-in-antidepressant-row/

I have no difficulty whatsoever believing that Dr Peter Gordon was Gaslighted.

I was prescribed antidepressants (not SSRIs) many many years ago, and I consumed them for maybe 6 years. They made no difference to my mood whatsoever and coming off them was no problem either.

BUT I have definitely suffered dreadful withdrawal on attempted discontinuation of strong Neuroleptics. However I did ultimately get off them and learn to accommodate my reactive “Anxiety”.

Thank you for sharing this James. I’m very sorry you’re still going through this, but it is so helpful to those of us who have been struggling for years with withdrawal and continue to do so to know we are not alone .

Excellent blog, James – a powerful personal story that educates and informs.